The Cosmic Tree

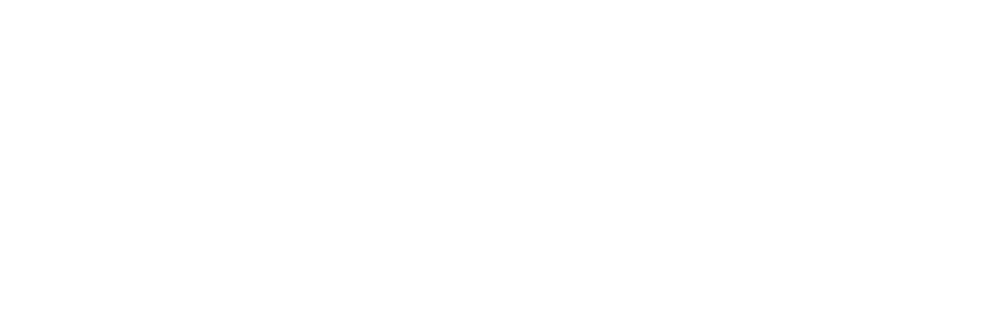

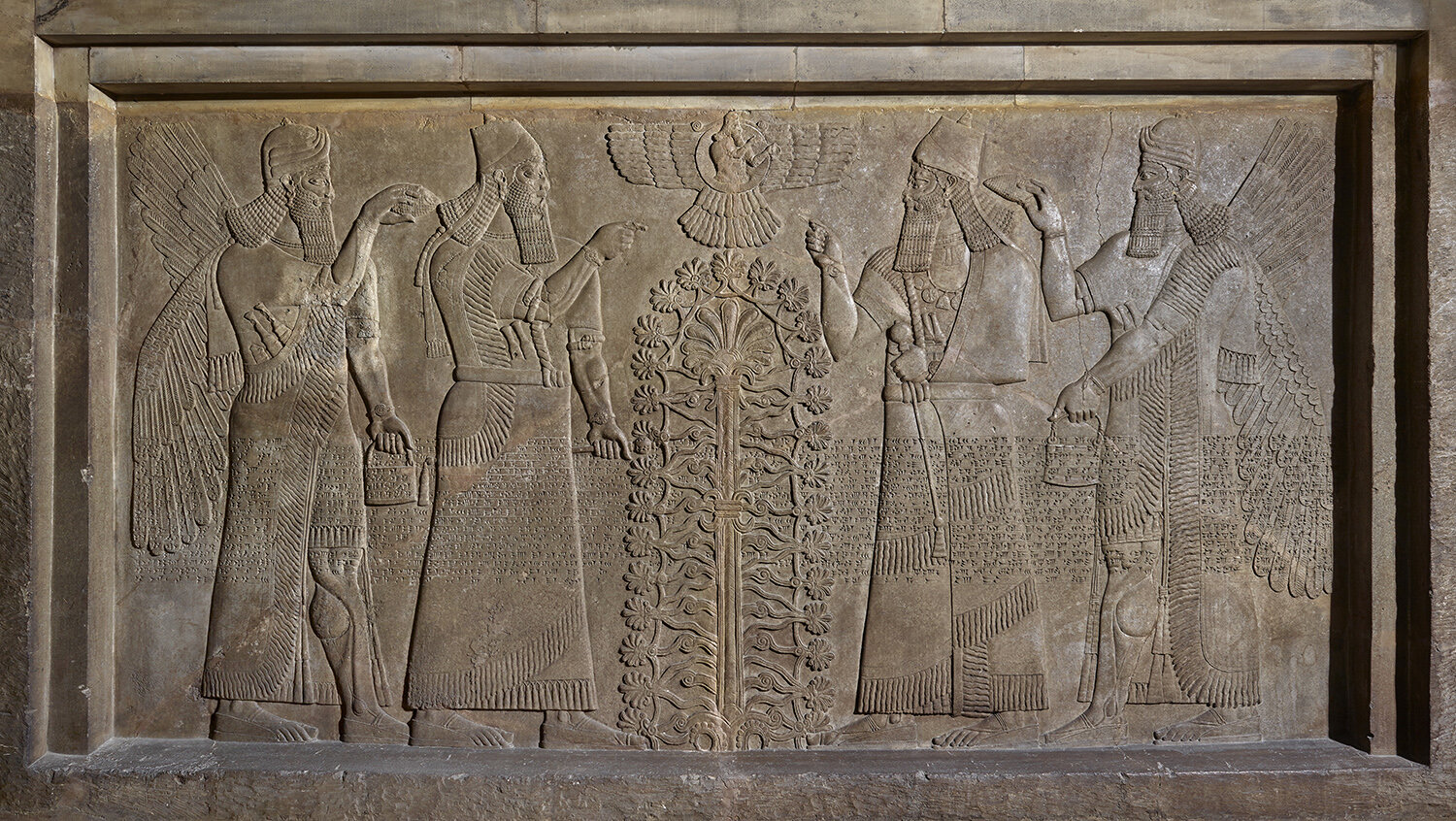

The Cosmic Tree is a universal archetype that appears in the symbolism and mythologies of countless civilisations. It represents the Axis Mundi, or World Axis, that connects every aspect of the universe. From the giant Ash Yggdrasil, that connected the Nine Worlds of Norse mythology, to the Islamic ‘Tree of Immortality’, and the ‘Tree of Knowledge’ in the Garden of Eden, again and again the human condition is connected to the physical and transcendental universe through the image of a plant. The motif of a sacred tree is often associated with the figure of a serpent – an emblem of the shamanic experience, ascending from the shadows to the spiritual plane.

The great Twentieth century psychoanalyst Carl Jung developed a deep understanding of the archetypes of the collective unconscious and how they emerge as symbolic images. He created an extraordinary manuscript - the Liber Novus - now commonly known as The Red Book, filled with symbolic images he discovered in the depths of his own mind. The tree was a recurring motif, pictured as both supporting and connecting every aspect of the cosmos. Planted in the earth its roots reach down through the terrestrial realm toward darkness and the shadow realm, whilst its branches stretch up through the celestial, toward the star-filled heavens.

Wall panel, relief, Neo-Assyrian, North West Palace. British Museum. © The Trustees of the British Museum

C.G. Jung, The Tree of Life

Canterbury Psalter. Manuscript, 12th century. Source: Bibliothèque nationale de France

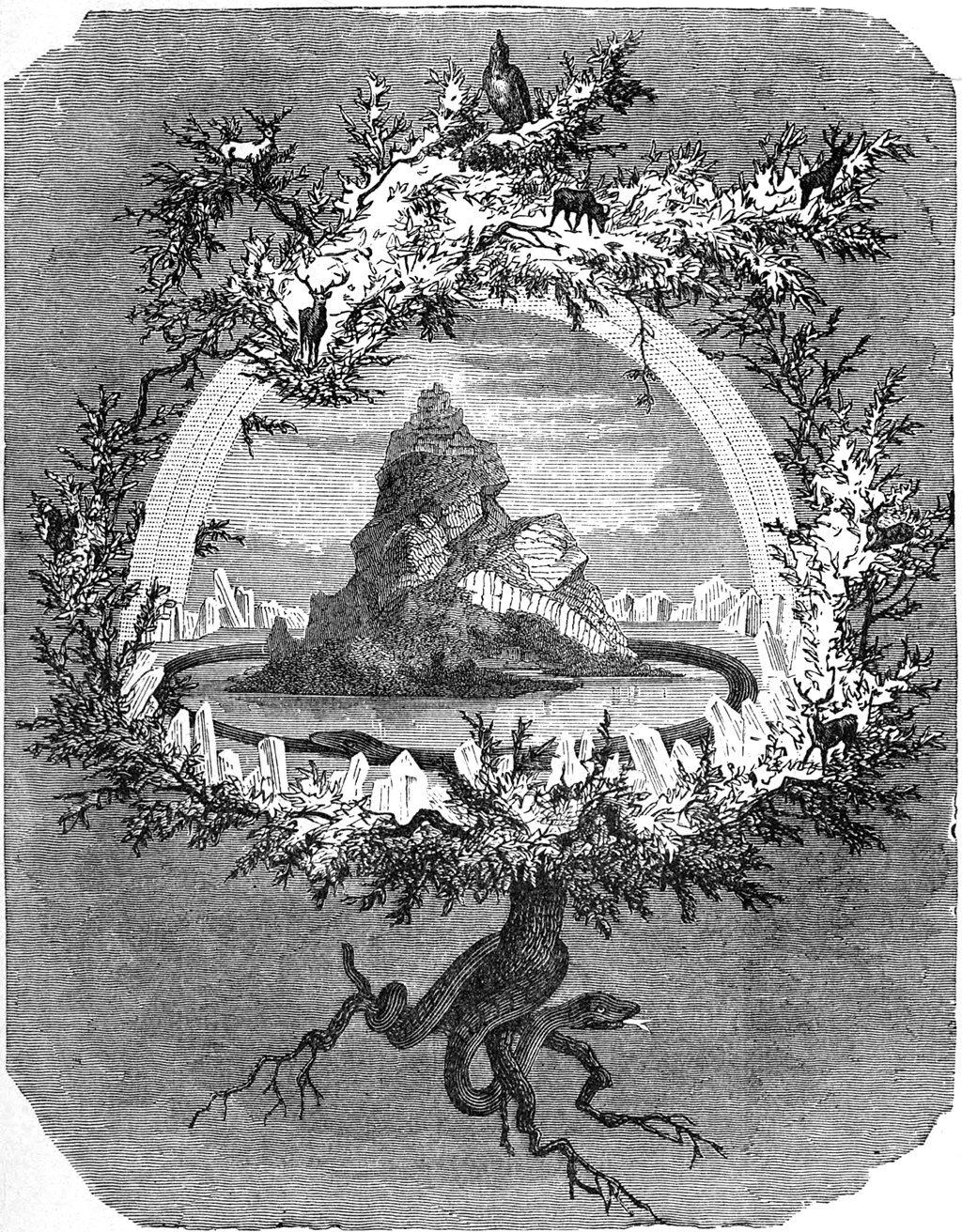

Delfina Muñoz de Toro, Vimi Yuve (Fruit of the Serpent), 2019. Watercolour on paper, 61 x 45.5 cm. Credit: courtesy the artist

C.G. Jung, Mandala 89

C.G. Jung, Systema Munditotus (The System of All Worlds), 1916

Tree of Life, Coromandel Coast, India, circa. 1760. Painted and dyed cotton, 318 x 212 cm. Prahlad Bubbar, London

Hilma af Klint, Tree of Knowledge, No 1, The W Series, 1913. Watercolour, gouache, graphite and metallic paint on paper. By the courtesy of the Hilma af Klint Foundation. Photo: Modern Museet, Stockholm

C.G. Jung, The Philosophical Tree

Jacob Meydenbach, Hortus Sanitatis, 1491. Illustration detail. Laurie Auchterlonie/Wellcome collection

Friedrich Wilhelm Heine, The Ash Yggdrasil. From: Asgard and The Gods: The Tales and Traditions of our Northern Ancestors, Forming a Complete Manual of Norse Mythology, 1886.

C.G. Jung, The Incantations 54

Athanasius Kircher, Serpent’s Descent, From Ars Magna Lucis, 1646. Public Domain

C.G. Jung, The Incantations 63

William Blake, Jacob's Dream, 1805. Pen and ink and watercolour

Alexander Tovborg

Photo: Andreas Rosforth

In his paintings, drawings, sculptures and performances Alexander Tovborg explores the roles that religion and mythology play in human identity and the world we inhabit. He has immersed himself in spiritual practices that range from Christian congregations, Cuban Santería rituals, an apprenticeship with a Japanese tea master, and working with a clairvoyant to explore his past lives.

Tovborg’s rich visual language borrows from symbolism found in ancient cultures, asserting the weight and power of images in religion, history and mythology - in the narratives we create to understand the past and make sense of where we find ourselves now.

In 2017, he visited Damanhur - a federation of spiritual communities founded in 1975 in the Valchiusella Valley, Italy. 600 people live there, united in an understanding of the environment as a conscious, sensitive entity, celebrating the rhythms of nature, the plant and animal realms, the practice of meditation and the study ancient magical traditions. With settlements dedicated to earth, water, fire and air, this eco-community is based on the values of ethical and sustainable living aligned with subtle energies in the universe, the elements and forces of the natural world. It has been recognised by the UN Global Forum of Human Settlements as a model for sustainable society and now has its own constitution, currency, and applications of science and technology as well as a thriving artistic culture that promotes the role of art in awakening divinity in human-nature. The Temples of Humankind are an extraordinary subterranean complex dug into a mountain-side – filled with symbolic images, mosaics, and stained glass, celebrating a ‘universal spirituality’.

In this spoken word account inspired by a personal diary entry, Tovborg narrates his encounters with the Damanhurian civilisation – their imagery and sense of place, the Temples of Humanity and their traditional ceremonies involving the sounds of gongs. These experiences inspired a monumental painting, Alter of Humanity in which he interrogates the binaries of sacred and profane, of spirit and matter. Images of serpents and dragons personify the transformational spirit of ‘Mammon’ – a term that refers to the false objects of worship that may be renounced to attain spiritual liberation.

Altars of Humanity, 2017. Watercolor, acrylic, crayon, felt, goldleaf and holy water on wood panels and bronze. Courtesy Blum & Poe

Linder

Linder’s photomontages often juxtapose images from fashion or domestic magazines, with archival or pornographic material. In recent work, she has turned to excavation as well as superimposition - delving into the buried histories of people and places and drawing on narratives from classicism, spirituality, myth and folklore. During a residency at Chatsworth House between 2017-18 she created a living installation in the grounds - a womb-like enclosure composed of curvaceous vegetal elements, rich in scent and colour. Situated close to the river, its structure is based on the moon gates that feature in Chinese or Japanese gardens – circular structures that mark symbolic thresholds. She found inspiration in the traces of female histories woven into the Chatsworth grounds including Queen Mary’s Bower - a surviving feature of the Tudor estate. In the 16th century, Mary Queen of Scots was confined at Chatsworth by the order of Queen Elizabeth I and this secluded area that may once have provided shelter or privacy to the banished queen.

In these two photo-collages, Linder has superimposed images of roses, shells and serpents over portraits of women in the Devonshire family lineage. The spiralling forms of mollusc shells adhere to sacred geometrical principals that can expand or contract in potentially infinite patterns. Time is inscribed in the shell’s materiality – extruded by the creature as it ages so that its outer form evidences the duration of its own life. The coiling form of the snake appears in countless religions, mythologies and cultures, to symbolise transformation, rebirth, immortality, transcendence and healing. In Greek mythology, Asclepius, the god of medicine, carried a caduceus – a wand or staff entwined with two serpents, Both Linder’s titles are names of Greek goddesses. Pythia is the high priestess of Apollo, the oracle of Delphi, and in this work, a portrait of Duchess Georgiana (who lived in a ménage à trois at Chatsworth with her husband and his mistress by Bess of Hardwick) is here masked by a coiled snake, alluding to the monster at the heart of the oracle, as well as biblical associations with the forbidden. The serpent is one of the primary symbols of Chatsworth and is also associated with the divine feminine energy in Kundalini, represented as a coiled snake at the base of the spine. In yogic and tantric practices, mystical experiences are sought by awakening this energy, allowing it to ascend through the chakras of the body to a cosmic blossoming symbolised by the thousand-petalled lotus on the crown of the head.

Linder, Eidothea, 2017. Photomontage. © Linder Sterling. Courtesy the artist and Modern Art, London

Linder, Pythia, 2017. Photomontage. © Linder Sterling. Courtesy the artist and Modern Art, London

Hildegarde of Bingen

Twelfth-Century Christian mystic Hildegaarde of Bingen was an ecological thinker – she understood the universe as an entity, each part penetrated by the essence of the whole and saw a radiance in creation – in the greening of the earth, the sprouting of seeds, and blossoming of plants. She called this verdant fecundity Viriditas, a ‘greening’ of the planet that is infused with a spiritual principle and a healing potential that can bring about planetary attunement. The Botanical Mind draws inspiration from Von Bingen’s cosmology – in her amalgamation of science, mysticism and art and her belief that images and music and have the potential to awaken humanity to mysterious truths of the universe.

Hildegarde von Bingen, Liber Divinorum Operum (The Book of Divine Works), 13th Century. Illuminated Manuscript. By concession of the Ministry for Cultural Heritage and Activities - Lucca State Library

Hildegarde von Bingen, Liber Divinorum Operum (The Book of Divine Works), 13th Century. Illuminated Manuscript. By concession of the Ministry for Cultural Heritage and Activities - Lucca State Library

Hildegarde von Bingen, Liber Divinorum Operum (The Book of Divine Works), 13th Century. Illuminated Manuscript. By concession of the Ministry for Cultural Heritage and Activities - Lucca State Library

Hildegarde von Bingen, Liber Divinorum Operum (The Book of Divine Works), 13th Century. Illuminated Manuscript. By concession of the Ministry for Cultural Heritage and Activities - Lucca State Library

Michael Marder on Hildegard of Bingen

In a forthcoming title Green Mass: The Ecological Theology of St. Hildegard of Bingen, Marder reflects on the significance of vegetal life in von Bingen’s theology. Her ‘language of plants’ was not bound by symbolism and allegory; it described the vegetal kingdom as a world infused with spirituality and understood religion, not only metaphorically, through the being of plants. The word play of Marder’s title alludes both to the most material and the mundane: the plant world representing the largest physical biomass on our planet and liturgical Church service belonging to the spiritual realm – immaterial, ethereal.

Marder collaborated with Swedish composer and cello performer, Peter Schuback, who has written a musical composition to accompany the book, each movement resonating with the themes of Marder’s chapters. Here we share Chapter 2: Analogies with the corresponding musical accompaniment by Peter Schuback.

Click here to read the Chapter 2 from Green Mass: The Ecological Theology of St. Hildegard of Bingen

Adam Chodzko

Adam Chodzko is an artist working across media, exploring our conscious and unconscious behaviour, social relations and collective imaginations through artworks that are propositions for aberrant forms of ‘social media’.

This new digital commission has been developed specially for The Botanical Mind. Working with computer coders, Black Shuck, Chodzko has developed an algorithm that searches for ciphers - signs and letters created for a secret language, the Lingua Ignotae, by the 12th Century Christian mystic Hildegard von Bingen. The algorithm scans footage of undergrowth, woodland and forest, looking for the ciphers in the shadows between and under the vegetation. Chodzko has assigned each character a sound, taken from the opening phrases of Hildegard’s choral compostions: O Viridissima Virga (O branch of freshest green) and O Frondens Virga (O blooming branch, you stand upright in your nobility, as breaks the dawn on high). Once located, the ciphers are sequenced to spell out names of plants she catalogued in her writing as well as deviating to create new hybrid plants.

Chodzko has speculated that this secret language – a code she developed some 900 years ago – might be received as a message to us now, or as a plan for the future. The work attempts to recover, mobilise and enact it as an ecstatic experience, generated through a system of channelling – of light, darkness, language, naming, plants and nature – a possible path toward an infinite Eden.

This is a clip from the work which plays out infinitely, in real time, and attempts to become an idea of botanical transformation – at once both a process and its experience.

Sarah Angliss

In a forthcoming podcast - Hildegarde Von Bingen - The Threads Of The Air - due to be released on June 19, musician Sarah Angliss draws on the botanical writing of Hildegard von Bingen, a twelfth-century Christian mystic, to help make sense of her own experiences of illness, healing and the turn of the season while the city is in lockdown. Sarah will immerse us in a sonic fever dream, using fragments of Hildegard’s texts on herbal medicine to explore her personal experiences of fever as she examines Hildegard’s ecstatic visions. She discusses how Hildegard’s progressive approach to washing rituals and the observation of nature reverberate through the ages. At a time when we’re facing a new pathogen that reveals the limits of modern medicine, it’s hard not to feel an affinity with people who experienced contagions in Hildegard’s time. We’re retreating to measures that would not have seemed unfamiliar to her, in the absence of a cure. This podcast features a score specially written by Sarah, which responds to Hildegard’s writing on The Threads of The Air - describing the purifying properties of the air as summer comes and goes.

Composer, performer and electronic artist Sarah Angliss creates finely-wrought music, hard to classify, where acoustic instruments, electronics and robotics, aiming to create a soundworld with a sense of the uncanny and a powerful emotional heft. “Music possessed of an eerie instability…a whole universe unto itself brimming with fresh propositions and new directions…a shimmering, minimalist masterpiece.” (The Wire Magazine).

Sarah Angliss’s highly inventive work reflects an eclectic musical background. A classically-trained composer and instrumentalist, who specialised early on in both electronics and ancient music, Sarah also has a background in biologically-inspired robotics. She combines these disciplines to create her highly distinctive soundworld. A prolific live performer, Angliss also applies her unusual sonic techniques to theatre. In 2018 Sarah received a Composer’s Award from the Paul Hamlyn Foundation.

Andrea Büttner

Andrea Büttner’s (b. 1972, Stuttgart, Germany) conceptually-oriented practice alternates between forms like the woodcut, which privilege the use of the hand and the rough interaction of materials, and research-based projects that delineate the broader contexts in which her ideas circulate. She has an open engagement with philosophical texts and her use of imagery at times evokes religious themes, particularly those associated with Catholic monastic traditions.

In these three series of images, artist Andrea Büttner reveals the now-overgrown planting-beds and greenhouses in a former Nazi concentration camp, contemplates the significance of moss as a cryptogram for smallness, shame and hidden sexuality, and the various appearances of potatoes in her work.

Moss / Littleness

“Since 2010 mosses have featured in various works and exhibitions of mine. Moss gathers where surfaces are left alone and is something small that can be found nearly everywhere. This “letting alone” would seem opposed to the demands of productivity. Moss is also a slang word for money in German. At first, my interest in moss was sculptural, but eventually I came to understand a connection between moss and shame. Being small and reproducing via spores, mosses have a hidden sexuality (this is the literal translation of the way biologists classify moss: as cryptogamous). Hidden sexuality has to do with shame. And smallness has to do with shame.”

Detail from Stereoscopic slide show from the Whitehouse collection (mosses and field trips), 2014, 160 analogue 35 mm slides. Photography: Harold and Patricia Whitehouse © National Museum of Wales.

Detail from Stereoscopic slide show from the Whitehouse collection (mosses and field trips), 2014, 160 analogue 35 mm slides. Photography: Harold and Patricia Whitehouse © National Museum of Wales.

Stereoscopic slide show from the Whitehouse collection (mosses and field trips), 2014, 160 analogue 35 mm slides. Installation View: Bergen Kunsthall, 2018. Photography: Thor Brødreskift. Courtesy Hollybush Gardens, London, David Kordansky Gallery, Los Angeles, and Galerie Tschudi, Zuoz. © Andrea Büttner / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2020.

Stereoscopic slide show from the Whitehouse collection (mosses and field trips), 2014, 160 analogue 35 mm slides. Installation View: Bergen Kunsthall, 2018. Photography: Thor Brødreskift. Courtesy Hollybush Gardens, London, David Kordansky Gallery, Los Angeles, and Galerie Tschudi, Zuoz. © Andrea Büttner / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2020.

Text by Ray Tangney, Principal Curator of Cryptogams at Amgueddfa Cymru – National Museum Wales. Commissioned by Andrea Büttner for a series of letterpress on paper works.

Littleness

Mosses are actually very successful plants and represent a different, rather than lesser, way of life. Their simple structures limit where they can grow – they can only grow where conditions suit them – but they are also able to grown in places where other plants can’t, for example, on rocks and other hard surfaces like bark, bricks, slate roofs, etc. Many mosses have evolved desiccation tolerance, and can withstand periods without water, beginning growth again after re-wetting.

Lower Plants

Mosses are also called lower plants, as they are small with simple structures. Because of this simplicity, they were considered by early botanists to represent a lower, imperfect level of development, compared to higher, or perfect, flowering plants. In terms of evolution they have been considered primitive, and the higher plants more advance.

Cryptogams

Mosses are cryptogams. Cryptogams are an important group of organisms that includes mosses and liverworts, lichens, fungi and algae. Cryptogams have reproduction that is not visible to the naked eye, and the Swedish botanist Linnaeus described them as having clandestine or hidden marriage, compared to the open or public marriage of flower plants.

Detail from Moos/Moss, 2010-13, series of photographs, dimensions variable. Photography: Andrea Büttner. Courtesy Hollybush Gardens, London, David Kordansky Gallery, Los Angeles, and Galerie Tschudi, Zuoz. © Andrea Büttner / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2020.

Detail from Moss Garden, 2014, mosses, powder-coated steel, tuff stones, ceramics, 15 x 180 x 120 cm. Photography: Andy Keate. Courtesy Hollybush Gardens, London, David Kordansky Gallery, Los Angeles, and Galerie Tschudi, Zuoz. © Andrea Büttner / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2020.

Research/production image: Moss Garden, Botanical Garden (Palmengarten), Frankfurt, Germany, 2014. Photography: Andrea Büttner. Courtesy Hollybush Gardens, London, David Kordansky Gallery, Los Angeles, and Galerie Tschudi, Zuoz. © Andrea Büttner / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2020.

Research/production image: Moss Garden, National Museum Cardiff, Wales, 2014. Photography: Andrea Büttner. Courtesy Hollybush Gardens, London, David Kordansky Gallery, Los Angeles, and Galerie Tschudi, Zuoz. © Andrea Büttner / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2020.

Research/production image: Moss Garden, National Museum Cardiff, Wales, 2014. Photography: Andrea Büttner. Courtesy Hollybush Gardens, London, David Kordansky Gallery, Los Angeles, and Galerie Tschudi, Zuoz. © Andrea Büttner / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2020.

Potato

“The potato appears often in my work – from glass paintings to woodcuts, and most recently as a ceiling painting – and I use it to speak about realism, about poverty, about Vincent Van Gogh and Courbet. I show potatoes to establish a distance from aesthetic ideas of high versus low, of elegance and intellectuality. The round form or lump is an element form of matter (bread, feces, money).”

Detail from Ceiling Painting (potato), 2019, gouache on gallery ceiling, dimensions variable. Photography: Andy Keate. Courtesy Hollybush Gardens, London, David Kordansky Gallery, Los Angeles, and Galerie Tschudi, Zuoz. © Andrea Büttner / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2020.

Detail from Ceiling Painting (potato), 2019, gouache on gallery ceiling, dimensions variable. Photography: Andy Keate. Courtesy Hollybush Gardens, London, David Kordansky Gallery, Los Angeles, and Galerie Tschudi, Zuoz. © Andrea Büttner / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2020.

Detail from Ceiling Painting (potato), 2019, gouache on gallery ceiling, dimensions variable. Photography: Roman März

Detail from Ceiling Painting (potato), 2019, gouache on gallery ceiling, dimensions variable. Photography: Andy Keate. Courtesy Hollybush Gardens, London, David Kordansky Gallery, Los Angeles, and Galerie Tschudi, Zuoz. © Andrea Büttner / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2020.

Detail from Ceiling Painting (potato), 2019, gouache on gallery ceiling, dimensions variable. Photography: Roman März

Detail from Tische (tables), 2013, tables, glass, tablecloths, pictorial and written material. Installation View: MK Gallery, Milton Keynes, England, 2013. Photography: Andy Keate. Courtesy Hollybush Gardens, London, David Kordansky Gallery, Los Angeles, and Galerie Tschudi, Zuoz. © Andrea Büttner / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2020.

Detail from Tischschmuck (table decorations),2013, cast bronze, multiple pieces. Photographer: Rory Moore. Courtesy Hollybush Gardens, London, David Kordansky Gallery, Los Angeles, and Galerie Tschudi, Zuoz. © Andrea Büttner / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2020.

Click here for an essay by Malin Ståhl on Andrea Buttner’s Untitled (potato).

Biodynamic Agriculture and National Socialism

“Last year I made a video, Karmel Dachau, about a Carmelite convent that was founded in 1964 adjacent to the Dachau Concentration Camp Memorial. I've known this convent since my childhood.

Next to the concentration camp memorial, former greenhouse structures and the concrete borders of plant beds still exist. They were part of the plantation at the Dachau concentration camp, where the prisoners had to work and were killed by labor. One of the purposes of the Nazi’s plantation was cultivate German drugs, German herbs, and to do research in biodynamic gardening.”

Former plant beds and greenhouses from the herb gardens and plantation at the Dachau Concentration Camp, 2019–2020, series of photographs, dimensions variable. Photography: Marion Schönenberger. Courtesy Hollybush Gardens, London, David Kordansky Gallery, Los Angeles, and Galerie Tschudi, Zuoz. © Andrea Büttner / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2020.

Former plant beds and greenhouses from the herb gardens and plantation at the Dachau Concentration Camp, 2019–2020, series of photographs, dimensions variable. Photography: Marion Schönenberger. Courtesy Hollybush Gardens, London, David Kordansky Gallery, Los Angeles, and Galerie Tschudi, Zuoz. © Andrea Büttner / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2020.

Former plant beds and greenhouses from the herb gardens and plantation at the Dachau Concentration Camp, 2019–2020, series of photographs, dimensions variable. Photography: Marion Schönenberger. Courtesy Hollybush Gardens, London, David Kordansky Gallery, Los Angeles, and Galerie Tschudi, Zuoz. © Andrea Büttner / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2020.

Still from Karmel Dachau, 2019, video. Courtesy Hollybush Gardens, London, David Kordansky Gallery, Los Angeles, and Galerie Tschudi, Zuoz. © Andrea Büttner / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2020.

Next chapter