As Within, So Without

In Carl Jung's concept of the archetypes, he perceived continuities between the forms of physical as well as psychic reality, essential patterns - regularities of form and structure - that appear in nature and arise naturally in the mind. The many mandalas that appear in his Liber Novus, or Red Book, were created with a method he called Active Imagination - an attempt to ‘form in matter’ his innermost thoughts and the structure of his psyche.

Kalachakra Mandala. Public Domain

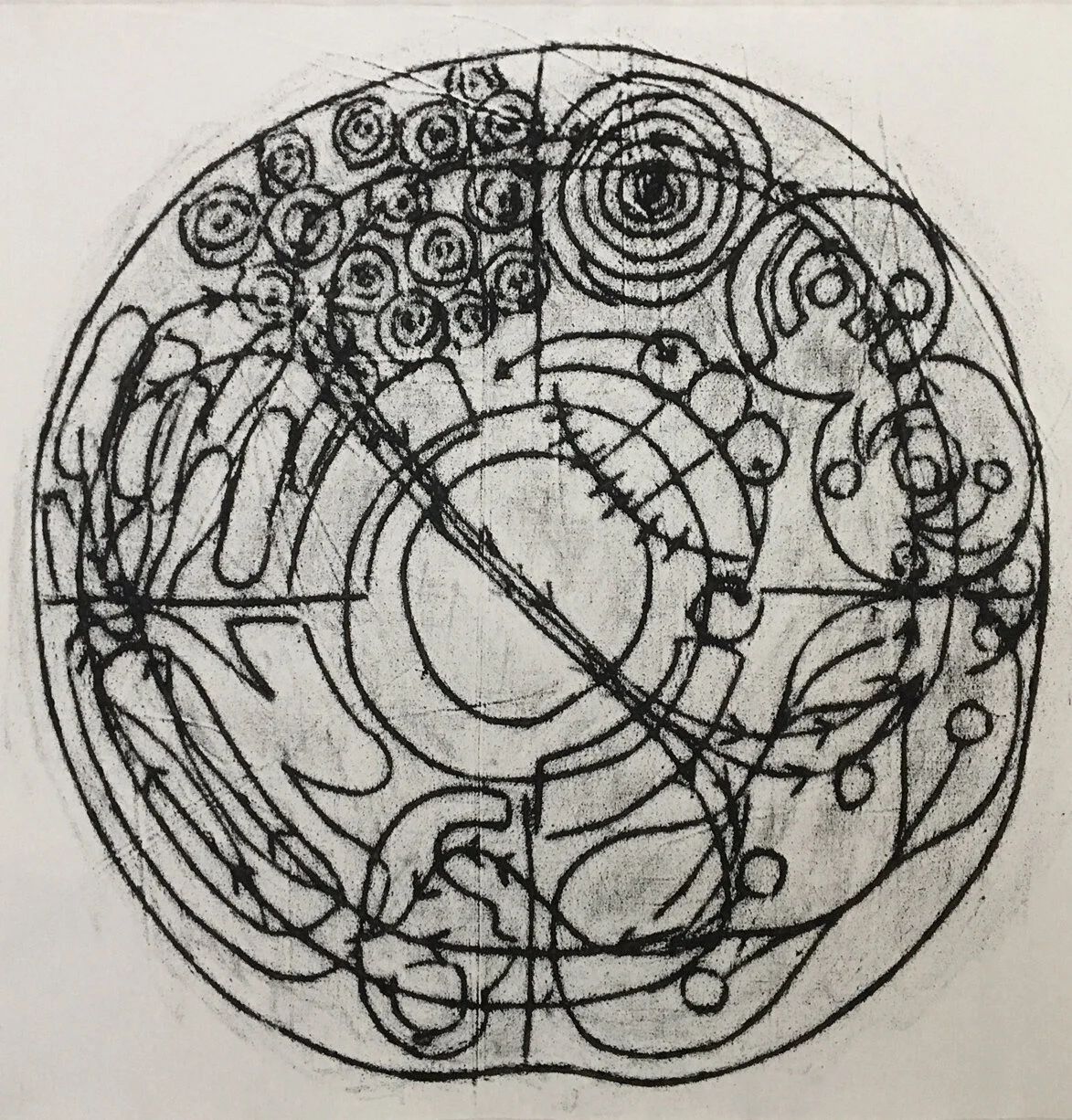

The mandala is one of the oldest spiritual symbols and an image which attempts to both represent the universe schematically – with the individual subject occupying the central position – whilst also operating as an active meditation device, a gateway enabling transformative states of consciousness. They are common to various traditions of eastern and western mysticism, but they have also been created by a number of contemporary and modern artists.

The popularised fractal or spiral geometries associated with the art and images of psychedelia, appear not only in the morphology of plants but in the visions induced by mind-manifesting plant medicines, like Psilocybin found naturally in certain mushrooms, Mescaline arising in the Peyote cactus or Dimethyltryptamine, a substance secreted naturally in the brain, and activated when drinking Ayahuasca. The mystical experiences invoked by psychoactive plants, as well as encounters with Eastern mysticism, became central to the counter-cultural revolution of the 1960s, exemplified in art, music and literature by figures like Bruce Conner, William Burroughs, Aldous Huxley and Brion Gysin.

Scholars have also speculated on the role of entheogenic plants in the evolution of consciousness and language, as well as the development of global religions, including that the mystical substance Soma in the ancient Indian Vedas was a psychoactive mushroom, and that the ritualistic use of psychedelic plants played a part in the development of Christianity.

John McCracken, Trebizonoum, 1972. Oil on canvas, 76.2 x 76.2 x 2.2 cm. Courtesy The Estate of John McCracken and David Zwirner

Adolf Wölfli, Der San Salvathor, 1926. Graphite, coloured pencil, crayon on paper, 148.6 x 210.8 cm. Courtesy of The Museum of Everything

Brion Gysin, Magic Mushrooms, 1961. Work on paper, 20 x 13 cm. Courtesy the Artist's Estate and October Gallery, London

Gemma Anderson, Garden of Forking Paths, 2019. Energy landscapes visualising potential pathways of amino acid chains forming folded proteins

Matt Mullican, 2nd generation cosmology rubbed on a large pillowcase, 2019. Oil stick rubbing on cotton, 80 cm X 80 cm. Courtesy the artist and Todoli Citrus Foundation

Henri Michaux, Untitled Chinese Ink Drawing, 1961. Ink on paper, 74.6 x 109.9 cm. Provenance Tate, Photo © Tate

Bruce Conner

Bruce Conner (1933-2008) was born in Kansas, in the American Mid-west, and became an important figure in post-war art and the west-coast counter-cultural movement through the 1960s and ‘70s. Well known for his landmark experimental films, his disciplines also spanned assemblage, drawing, sculpture, painting, collage, and photography. Motivated by mysticism, spirituality and psychedelia, his visionary works were often filled with dark subject matter, symbolic and religious imagery.

“A genius of the recondite and the banal, of occult disciplines and popular culture, he possessed the third or inner eye, meaning he was capable of microscopic and macroscopic vision, of delving into the visceral while attaining a state of illumination”. John Yau, An Artist Who Possessed a Third Eye, Hyperallergic, July 9, 2016.

Bruce Conner, PSYCHEDELICATESSAN OWNER, March 31, 1990. Collage of found illustrations, 21.5 x 18 cm. Collection of Amy Gold and Brett Gorvy

LOOKING FOR MUSHROOMS, 1959–67/1996

One of Conner’s first departures from the found material that constituted his earlier works, LOOKING FOR MUSHROOMS is a visionary travelogue including footage of journeys Conner and his wife Jean made in Mexico, as well as scenes of their life in San Francisco. Between 1961 – 62 while he and Jean were living in Mexico City, they ventured into the rural landscapes to look for psychedelic mushrooms, on at least one occasion accompanied by Timothy Leary who appears on camera. The original version was shown as a loop, with a soundtrack by the Beatles. Conner revisited it in 1996, repeating each frame five times, stretching the footage out to fourteen-and-a-half minutes and accompanying it with a soundtrack composed and performed by experimental musician Terry Riley. The, at-times dark, subject matter combined with rapid rhythm, multiple-exposure sequences and strobe effects, evokes an atmosphere of meditation or perhaps even a psychedelic experience, in which subliminal images are allowed space to arise within the mind.

Between 22 - 29 June, in collaboration with Paula Cooper Gallery, Camden Art Centre presented a week-long viewing of Conner’s seminal film LOOKING FOR MUSHROOMS (1959-67/1996).

Trailer for: Bruce Conner, LOOKING FOR MUSHROOMS 1959-67/1996 Digitally restored, 2016. 16mm, colour, sound, 14.5 min. © Conner Family Trust, San Francisco. Courtesy Paula Cooper Gallery, New York

Bruce Conner UNTITLED D-8, July 18, 1965. Ink on paper, 15 x 15 cm, Collection of Amy Gold and Brett Gorvy

Bruce Conner MANDALA, July 18, 1968. Ink on paper, 25.5 x 25.5 cm Collection of Amy Gold and Brett Gorvy

Inkblot drawings

Conner’s inkblot drawings are one of his most expansive series, and were exhibited in the 1997 Whitney Biennial. Begun in 1975 he continued making them throughout his career, adopting the method as his main artistic output in the last decades of his life. His meticulous process involved marking and scoring a page, folding it along parallel vertical lines, then applying ink before folding the paper – a moment in which, for Conner, ‘a miracle occurs’. For him, the parallel lines created series that had relations to one another, through which variation and chance became apparent. He compared this formal device to the medium of film - a succession of images that engages the faculty of memory and the mind’s awareness of change: ‘The goal is to create objects that continually renew themselves, to always change, to have the potential for the process of change’. In the inkblots, intricate patterns proliferate through symmetrical mirroring and chance effects, generating seemingly infinite permutations that have an affinity with the self-generative behaviour and symmetrical bifurcation of plant forms. Reflecting on the significance of symmetry, Conner said ‘The awareness of symmetry is probably ingrained into our consciousness. And as soon as you see symmetry, it is interpreted. It is part of the balance and patterns of nature; minerals, animals, plants, planets… It appears in Renaissance paintings and other art forms through all of the centuries. It’s in textiles and rugs.’

All citations taken from an interview between Bruce Conner and Jack Rasmussen in After Bruce Conner: Anonymous. Anonymouse, and Emily Feather, published by the American University Museum, Anaconda Press, 2005

Bruce Conner, INKBLOT DRAWING (5/13/93), 1993, Pelikan ink and YES glue with photocopy

23 1/16 x 21 7/16 in. (58.6 x 54.5 cm). Photo: Steven Probert © 2020 Conner Family Trust, San Francisco / Artists Rights Society (ARS). Courtesy Paula Cooper Gallery, New York.

Bruce Conner, INKBLOT DRAWING, August 25, 1994. ink on paper. 11 1/4 x 7 1/2 in. (28.6 x 19.1 cm). Photo: Steven Probert © 2020 Conner Family Trust, San Francisco / Artists Rights Society (ARS). Courtesy Paula Cooper Gallery, New York

Bruce Conner, INKBLOT DRAWING, January 2, 1993. ink on paper. 11 1/2 x 7 1/4 in. (29.2 x 18.4 cm). Photo: Steven Probert © 2020 Conner Family Trust, San Francisco / Artists Rights Society (ARS). Courtesy Paula Cooper Gallery, New York

Bruce Conner, INKBLOT DRAWING APRIL 6, 1995, 1995. ink on paper. 9 1/2 x 9 1/2 in. (24.1 x 24.1 cm) Private Collection. Photo: Steven Probert © 2020 Conner Family Trust, San Francisco / Artists Rights Society (ARS). Courtesy Paula Cooper Gallery, New York

Bruce Conner, INKBLOT DRAWING OCTOBER 1991, 1991, ink on paper. 22 1/2 x 30 3/8 in. (57.2 x 77.2 cm). Photo: Steven Probert © 2020 Conner Family Trust, San Francisco / Artists Rights Society (ARS). Courtesy Paula Cooper Gallery, New York

Bruce Conner, UNTITLED INKBLOT DRAWING, SEPTEMBER 18, 2000, 2000, ink on paper, 6 x 6 5/8 in. (15.2 x 16.8 cm). Photo: Steven Probert © 2020 Conner Family Trust, San Francisco / Artists Rights Society (ARS). Courtesy Paula Cooper Gallery, New York

Bruce Conner, TRIO 31-29-32, 1975 ink each card: 6 x 4 in. (15.2 x 10.2 cm) Photo: Steven Probert. © 2020 Conner Family Trust, San Francisco / Artists Rights Society (ARS). Courtesy Paula Cooper Gallery, New York

Bruce Conner, INKBLOT DRAWING JUNE 5, 1975, 1975, ink, 6 x 4 in. (15.2 x 10.2 cm). Photo: Steven Probert. © 2020 Conner Family Trust, San Francisco / Artists Rights Society (ARS). Courtesy Paula Cooper Gallery, New York

Bruce Conner, INKBLOT DRAWING AUGUST 4, 1975,

ink 6 x 4 in. (15.2 x 10.2 cm). Photo: Steven Probert © 2020 Conner Family Trust, San Francisco / Artists Rights Society (ARS). Courtesy Paula Cooper Gallery, New York

Joachim Koester

My Frontier Is an Endless Wall of Points (After the Mescaline Drawings of Henri Michaux), 2007

16mm film animation [10:24]

Joachim Koester (b. 1962)’s conceptual practice in film, photography and sound could be seen as a persistent enquiry into apparent reality and a quest to uncover hidden aspects of perception. The narratives in his work reveal a fascination with mysticism and the occult, the more surreal moments from our cultural and social histories, leading us into strange and unfamiliar territories.

In the nineteenth century exploration was geographic - journeys made into impenetrable jungles or the ice deserts of the Arctic in an attempt to map the last “white” spots on the globe. But in the twentieth century this notion of the “unknown” changed. Exploration turned inward. The new realms to be discovered were the molecule (Niels Bohr), the unconscious (Sigmund Freud), language (Gertrude Stein) or the outskirts of the mind (Henri Michaux).

My Frontier Is an Endless Wall of Points is a film animation created from the mescaline drawings of Henri Michaux. Of all Michaux’s work, these drawings are most frequently described as “a venture into foreign territory.” Koester’s film is an exploration of a vast world on the borderline of words, a journey into a plant alkoloid to explore an interior territory (of plant and mind) in the forms of Michaux’s rapidly moving images.

My work is an attempt to literally animate this idea. I examine the traces of this journey in a series of rapidly moving images, making what could be termed a “psychedelic documentary.”

Joachim Koester

Joachim Koester and Stefan A. Pedersen

Insect Silver Noir 2018, sound piece, 18 minutes

The meditation Insect Silver Noir is a trance-like tour of changing embodiments and perspectives. It will take you to a dissident memory palace of plants, an insect, things that shine and things that are dark.

It is recommended that you use headphones and find a relaxing place free of disturbances, preferably where you can lie down, before listening to the sound piece. The file must not be played while driving a car, or similar activities that demand your full attention.

Stefan A. Pedersen (b. 1979) is an artist, musician and teacher working from Copenhagen, Denmark. In his work he seeks-out unstable relations between past and present moments, with the conviction that history is not causal or already given. His practice covers photography, moving image, sound, writing and some more performative forms within the group Ectoplasmic Materialism.

Terrence McKenna

Terence McKenna (1946 – 2000) was an American writer, philosopher, ethnobotanist and psychonaut. He grew up in a Colorado cattle and coal town, Paonia. In 1965 he found his way to San Francisco, enrolling in the University of California at Berkeley where he completed a self-tailored degree in ecology, resource recovery and shamanism. McKenna went on to study the ontological foundations of shamanism and the ethnopharmacology of spiritual transformation for a quarter century, advocating paths of shamanism and the use of hallucinogenic substances (primarily plant-based psychedelics) as a means of increasing many forms of human awareness. An innovative theoretician and spellbinding orator, McKenna emerged as a powerful voice for the psychedelic movement and the emergent societal tendency he called the Archaic Revival.

Forces and Fictions

Raymond Foye

In this text for Terry Winters: Paintings and Drawings, 2006, Raymond Foye captures the ‘floating thoughts’ that arise when standing in front of a painting – intimations that emerge before thoughts crystalise into language, situating painting as the “embodiment of consciousness, a blueprint for living, seeing, knowing, understanding and acting in the world”. Reflecting not only on Terry Winters but Brion Gysin and William Burroughs, he contemplates indeterminacy, the seen and unseen and the ways artists attempt to map the patterns, forces and dynamics that shape the world.

Installation view, The Botanical Mind: Art, Mysticism and The Cosmic Tree at Camden Art Centre, 2020. Photo: Rob Harris

The Alchemical Image

Raymond Foye

Harry Smith, Untitled Drawing, Ink on napkin

In this essay, originally published in The Heavenly Tree Grows Downward (2002), Raymond Foye discusses the work of Harry Smith (1923–1991) in the context of Philip Taaffe and Fred Tomaselli –

“…two artists for whom Smith is a crucial link to a wide and uncannily similar set of concerns. The painters Philip Taaffe and Fred Tomaselli have separately explored a great many of the themes central to Smith’s aesthetic: an examination of the nineteenth century metaphysical origins of abstract art that began with German Idealism and the concept of the Sublime, and extended to the practices of spiritualism and Theosophy; a renewed interest in the nineteenth–century botanical and zoological illustrations of Karl Blossfeldt and Ernst Haeckel, whose depictions of idealised forms and generative growth exerted a crucial influence on the early practitioners of abstraction; an engagement with folk art and traditional music as repository of vital forms and primordial impulses; a familiarity with the symbolic languages of medieval and Renaissance magic and cosmology; a search for connected cultural patterns in diverse anthropologies; and an abiding interest in the visual evocations of trance states as induced by psychoactive plants and neurostimulants—to name just a few of the more pronounced subjects in the work of these three artists.”

Jordan Belson

“I’m trying to focus on something, bring it back alive from the uncharted areas of the inner image, inner space. Intuition is the basis of my aesthetic judgement. The more you allow intuition to speak to you, the closer you are to the truth, and the origins of the universe. “

Jordan Belson

Jordan Belson (1926 - 2011) made paintings from a young age and later became known as one of the most important artists in 20th century avant-garde cinema and visual music. He was interested in expansive states of consciousness, devoting himself to a meditation practice and experimenting with hallucinogens. His films and paintings convey the inner images of his mind’s eye, of altered psychic states. He sought universal truths by voyaging inwardly, through meditation, to discover primary forms – circles, spheres, squares, pentagrams, hexagons - that also appear in sacred art, in Tibetan mandalas and tantric paintings.

Belson was a mystic who combined the spiritual with the scientific, with geometry and physics. His paintings and films are filled with dynamic and abstract forms that could equally emerge in the nebulous forms of deep space phenomena, the celestial, as well as in the sub-atomic realm or the immaterial expanses of the mind.

Jordan Belson, Untitled c. 1950. Oil, enamel, and wax on paper mounted to board in artist's frames. © Estate of Jordan Belson, Courtesy Matthew Marks Gallery

Jordan Belson, Untitled c. 1950. Oil, enamel, and wax on paper mounted to board in artist's frames. © Estate of Jordan Belson, Courtesy Matthew Marks Gallery

Jordan Belson, Untitled c. 1950. Oil, enamel, and wax on paper mounted to board in artist's frames. © Estate of Jordan Belson, Courtesy Matthew Marks Gallery

Jordan Belson, Untitled c. 1950. Oil, enamel, and wax on paper mounted to board in artist's frames. © Estate of Jordan Belson, Courtesy Matthew Marks Gallery

Music of the Spheres, 1977

In this film, Jordan Belson has based his imagery on the ancient Greek conception of the solar system as one vast musical instrument, “the seven stringed lyre of Apollo”. The abstract, cosmic images produced by the order of mathematics and space connect with the earthly world we know. Flowing, hypnotic movements of form and colour create a mesmerising visual experience – another level of reality in which the music fuses with the images to become an integral whole.

“There is geometry in the humming of the strings. There is music in the spacing of the spheres”.

Pythagoras, 5th C. BC

From a Pyramid Films educational resource, 1977. Collection Center for Visual Music.

Jordan Belson, Music of the Spheres (stills), 1977. 16mm film transferred to HD video. Courtesy Center for Visual Music

Jordan Belson, Music of the Spheres (stills), 1977. 16mm film transferred to HD video. Courtesy Center for Visual Music

Jordan Belson, Music of the Spheres (stills), 1977. 16mm film transferred to HD video. Courtesy Center for Visual Music

Jordan Belson, Music of the Spheres (stills), 1977. 16mm film transferred to HD video. Courtesy Center for Visual Music

Non-Objective Film: The Second Generation (Excerpt) by William Moritz

Originally published in Film as Film, Formal Experiment in Film, 1910 - 1975. London: Hayward Gallery/Arts Council, 1979. Courtesy and © Center for Visual Music

...Of all the early pioneers, Fischinger alone pursued non-objective film-making until the post-World-War-II period, and since he emigrated to America in 1936, he brought the living force of abstraction to a younger generation that included the Whitney brothers, Jordan Belson and Harry Smith...

The closest to Fischinger of these younger artists is Jordan Belson, who turned from non-objective painting to film-making after seeing Fischinger's films at the Art in Cinema festival at the San Francisco Museum of Art in 1946. In those years, Belson, living in North Beach near City Lights Bookshop, was part of the exciting movement publicized as the Beat Generation — full of Dizzy Gillespie's jazz, marijuana and Zen Buddhism. Belson's early films exhibited an extraordinary joie de vivre as well as considerable technical ingenuity and the exquisite sense of colour, form and movement that also distinguishes his later films.

To take two examples from these early films, Bop Scotch consists of single-frame images of objects on ordinary sidewalks, but photographed so carefully in such a well-planned sequence that the objects seem to assume living form, moving and flowing into one another (which foreshadows Hirsh's Defense d'Afflicher and Conner's Looking for Mushrooms), something that strongly suggests the Buddhist respect for the spiritual identity of all matter, but which could easily be accepted as a McLaren-like romp. Raga consists of beautiful, complex patterns which were painted on scrolls and planned in such a way that while the scroll was unrolled and drawn past a kaleidoscope in real time, the circular multiplication of the image by the mirrors created an ever-metamorphosing mandala. Again, even though this film exhibits a wide range of astonishing and spiritually moving images (including quick disappearances of images to produce lingering after-images, and bi-directional movement of circles both imploding and exploding at the same time), Belson felt that the basic kaleidoscope technique was too obvious, and tended to make the film appreciable as a technical rather than spiritual phenomenon. It took considerable courage and artistic integrity for Belson to withdraw these films from circulation.

In the late 50s, he collaborated with the electronic composer Henry Jacobs to produce the Vortex Concerts at Morrison Planetarium in San Francisco — a prototype for later light-show work. Jacobs arranged electronic scores by various composers, and Belson prepared multi-projector non-objective visuals using filmed materials by James Whitney, Hy Hirsh and himself. [1]

The experience of these light-shows, coupled with his growing spiritual devotion and mastery, caused Belson to withdraw his early films from circulation (because they imperfectly expressed his spiritual ideas, he felt), and to go into seclusion while he perfected a new non-animation, real-time system for image production (including grids, reflections, re-photography and other light-show devices), and a new expertise with recording equipment that allowed him to compose his own electronic scores for his films. Starting with Allures (1961), Belson began producing his Great Work, a series of films, continuing to the present, which establishes a personal audio-visual language — a goal that Eggeling and Fischinger had already longed for; but though Fischinger laid his personal stamp upon certain visual elements like the comet-crescent and the concentric circle alignment, no other non-objective film-maker has successfully developed an articulate non-verbal language to the extent or complexity of Belson.

The first ten films of his series function as definitions and expositions of certain phenomena, experiences and concepts — largely focused on mystical-spiritual and speculative-scientific issues (like Fischinger, but entirely independent of him).[2]

In his most recent two films, Cycles and Music of the Spheres, Belson has begun to discuss and interbreed his ideas — using, for example, a brief clip from Light to signify perceptual phenomena or light-energy transmission, a bit of Chakra to signify some point in raising consciousness through kundalini yoga, a glimpse of Samadhi for ecstasy, etc. — but blending them together in new combinations, mixing them with new imagery (sometimes live-action shots modulated through video mix or optical printing) to produce completely fresh insights. Cycles is dominated by a recurrent 'new' image of liquid matter swirling very slowly with one 'drop' or particle breaking away and rising from the main body (con-comitantly suggesting a yin-yang icon). Every time it recurs, this cycle is given a different visual quality and is matted with other information (including signifier 'quotes' from the preceding members of the series). Gradually it yields an invocation of the four elements of classical alchemy — earth, air, water and fire — each with a characteristic texture (e.g. square grid for earth, etc.) and each evolving into a mixture or blend with the next through integrative imagery (e.g., a circle of sky-divers = earth through air, and later, by juxtaposition with the circle/sun icon, = earth through air and water making fire, etc).

Having attempted to describe Belson's films, it should be admitted that one characteristic of a non-verbal language, of course, is that it can express and discuss things which cannot easily, or at all, be expressed in words, and indeed one of Belson's professed motivations for making non-objective films is to transcribe and communicate mystic visions and states of consciousness he has experienced in his spiritual exercises and cannot communicate otherwise.

Belson uses every cinematic device — sound and visual — to portray his concepts, and he manages to charge each device with undeniable and special meaning. Allures, for example, is structured in three parts, an opening optical invocation (in which a series of visual ambiguities and illusions 'exercise' the eyes and visual processing center of the brain, cf. the bodily exercises of yoga), a sequence of hard-edged Fischinger-like animations (accompanied by echoes of nostalgic music from the European cultural heritage) which serves as an 'earthly' preface to the dynamic energies and electronic sounds of the main body of futuristic, nuclear-cosmic imagery. Within this structure, Belson weaves a network of visual phenomena which refer back and forth to each other. The after-images from streaking figures or colour flickers — including the black circle described by the rolling, shrinking bar (which itself flickers appealingly in movement through a 'hitch' in our persistence of vision, the very foundation of cinematic illusion) become part of a network of positive/negative space/time phenomena — for which the meaning, like the 'unreal' fluorescent colours in the off-on flickering disc, are spontaneously generated in the mind of the viewer. Belson manages to integrate even the black/'silent' (in Cage's sense) spaces between his visual phrases, with dwindling after-images that lead to reflexive contemplation of the viewer/self as instrument vs. performer; and he interrupts some of Allures' most sentient moments with raw reminders of the nature of the film's material process — like the scratch into the film emulsion which appears (wittily accompanied by a giggle from the pop surfing song Wipe Out) during the black section that divorces the exercise-preface from the second, 'earthly' sequence, which in turn is echoed by a rough break in the film's negative during the most intense activity near the film's end, thus, like the cracks in raku pottery, keeping us from surrendering to the ease of formulated surface beauty.

[1] (2020 note) These filmed materials were very brief fragments, not whole films. Belson also used projected patterns and other source materials, not just film fragments. For more about the Vortex concerts please visit the bibliography at www.centerforvisualmusic.org/Belsonbiblio.htm

[2] (Moritz’s original note) For a general introduction to these ideas which are so important to many non-objective film-makers and painters, see Fritjof Capra's The Tao of Physics (Shambhala Press, Berkeley, 1975).

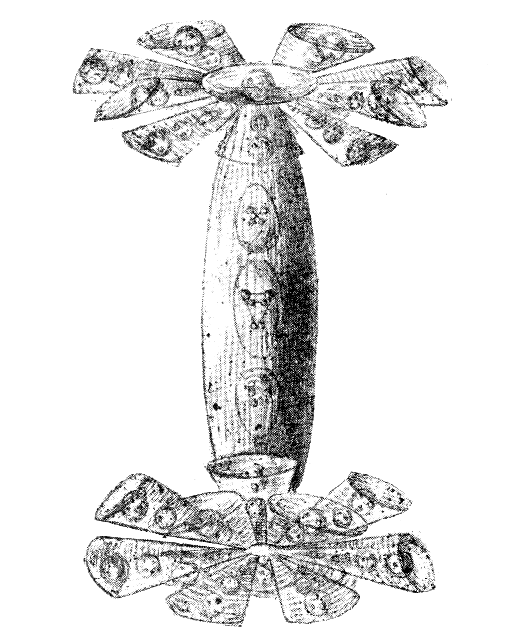

Annie Besant and Charles Leadbeater

In the early 20th century, Theosophists Annie Besant and Charles Leadbeater developed an “Occult Chemistry” in which they intuited the constituent shapes of matter at the atomic level by concentrating the mind in meditation.

Excerpts from Annie Besant and Charles Leadbeater, Thought-Forms: A Record of Clairvoyant Investigation, 1901

“Let us turn now to the second effect of thought, the creation of a definite form. All students of the occult are acquainted with the idea of the elemental essence, that strange half-intelligent life which surrounds us in all directions, vivifying the matter of the mental and astral planes. This matter thus animated responds very readily to the influence of human thought, and every impulse sent out, either from the mental body or from the astral body of man, immediately clothes itself in a temporary vehicle of this vitalised matter. Such a thought or impulse becomes for the time a kind of living creature, the thought-force being the soul, and the vivified matter the body. Instead of using the somewhat clumsy paraphrase, “astral or mental matter ensouled by the monadic essence at the stage of one of the elemental kingdoms”, theosophical writers often, for brevity's sake, call this quickened matter simply elemental essence; and sometimes they speak of the thought-form as an elemental." There may be infinite variety in the colour and shape of such elementals or thought-forms, for each thought draws round it the matter which is appropriate for its expression, and sets that matter into vibration in harmony with its own; so that the character of the thought decides its colour, and the study of its variations and combinations is an exceedingly interesting one.”

General Principals

Three general principles underlie the production of all thought-forms:

Quality of thought determines colour

Nature of thought determines form

Definiteness of thought determines clearness of outline

Forms Built by Music

… Many people are aware that sound is always associated with colour - that when, for example, a musical note is sounded, a flash of colour corresponding to it may be seen by those whose finer senses are already to some extent developed. It seems not to be so generally known that sound produces form as well as colour, and that every piece of music leaves behind it an impression of this nature, which persists for some considerable time, and is clearly visible and intelligible to those who have eyes to see. Such a shape is perhaps not technically a thought-form – unless indeed we take it, as we well may, as the result of the thought of the composer expressed by means of the skill of the musician through his instrument.

Next chapter