Astrological Botany

The intrinsic connection between geometry, music and the earthly and astral realms has been contemplated by European philosophers and artists since antiquity. Stretching back to Pythagoras in the 6th century BC, the idea of a ‘Music of the Spheres’ prevailed in Europe until the Renaissance – a correspondence across all aspects of the universe, an implicit harmony, mathematical in principal, figured as an act of music.

The Voynich Manuscript, 15th or 16th century. Courtesy Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library

Hildegarde von Bingen, Liber Divinorum Operum (The book of divine works), 13th Century. Illuminated Manuscript. By concession of the Ministry for Cultural Heritage and Activities - Lucca State Library

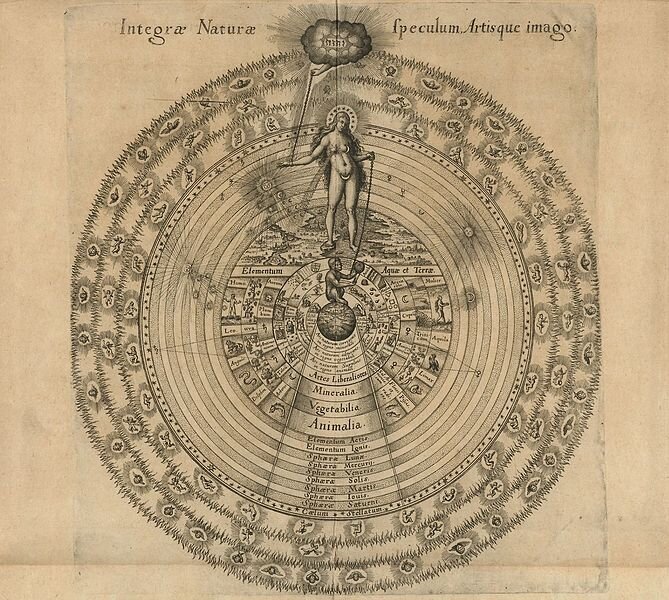

Robert Fludd, Detail from Utriusque cosmi maioris scilicet et minoris Metaphysica, physica atque technica Historia, 1617-21. Public Domain

The Voynich Manuscript, 15th or 16th century. Courtesy Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library

Robert Fludd, Detail from Utriusque cosmi maioris scilicet et minoris Metaphysica, physica atque technica Historia, 1617-21. Public Domain

Before the scientific revolution, the medieval European world view was built around these sympathetic and intuitive relationships – a natural science based on intimate, lived knowledge and equivalence and balance with nature. Correspondences between movements in the celestial realm and the properties of the material world, the so-called principles of ‘As Above, So Below’, or ‘As Within So Without’, informed a practice of plant-medicine based on the humours of the body. These alchemical principles – which were often understood in musical terms – were revealed in the cosmological drawings and illuminated manuscripts of mystics and thinkers like the 12th century German abbess Hildegarde von Bingen, the Jesuit scholar and polymath Athanasius Kircher, and the unknown author of the mysterious Voynich Manuscript – an extraordinary Renaissance codex, written in a still-undeciphered language. The manuscript was discovered in 1912 and appears to be a pharmacopoeia: an esoteric book of medicine bringing together herbal, cosmological, pharmaceutical and astrological wisdom.

With the advent of the ‘Age of Enlightenment’ in the late 17th century and the advance of scientific materialism, many of these ideas were driven underground – hidden for centuries in the arcana of the occult – subject to the same colonial values of ‘reason’ and ‘progress’ that destroyed indigenous cultures abroad. But they would resurface in the 20th century in works by a number of outsider, surrealist and modernist artists including Anna Zemankova, Adolf Wölfli, Hilma Af Klint, Ithell Colqhoun, Eileen Agar, and Anni and Josef Albers.

In 1912, the rare book dealer Wilfrid Voynich discovered what is now known as the Voynich Manuscript in a Jesuit library at the Villa Mondragone near Rome. Since then, historians have traced its history all the way back to the court of the Holy Roman Emperor Rudolph II at Prague circa 1600 –1610 — but no further. Its vellum has now been dated at 1404 to 1438 with 95% certainty, but its author, origin, purpose, contents, and provenance before 1600 all remain resolutely unknown. Not a single word of it has yet been successfully deciphered.

In this publication by The Serving Library, selected pages of the manuscript are reproduced along with an essay that explores the knowns and unknowns about this mysterious document, including its associations - some speculative, some evidential - with John Dee, Athanasius Kircher, and Roger Bacon. With thanks to the Beinecke Rare Books Library at Yale University.

Gaia and the Alchemical Tree of Life

Stephan Harding

Modern brain science has shown that we humans have two quite distinct ways of understanding our world. One, associated largely with our brain’s left hemisphere, is rational and reductionist, operating under the sway of linear logic, cause and effect thinking and sensorial attention to detail. This approach has given us science with all its benefits and pitfalls and tends to immerse us in the experience of being detached observers fundamentally disconnected from a world devoid of meaning and purpose. Our other way of seeing – the imaginal - is mostly associated with our right cerebral hemisphere and couldn’t be more different. It sees the world with an embodied openness by means of empathy, intuition and feeling and contemplates nature as a series of flowing images full of life and meaning. But this is far too simplistic a model, for, as Iain McGilchrist points out, we need both hemispheres to imagine and to reason. Each hemisphere offers us different views of the world which we combine in many ways: the left hemisphere narrowly focused on isolated lifeless objects, the right empathically connected with the unique individuality of every living being.

These two aspects of ourselves were disconnected from each other during the scientific revolution of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries when the rational was favoured and the imaginal was denigrated, giving rise to the severe global ecological, climate and psychological crises we face in our times. Out task now is to re-envision and heal the world by reuniting these opposites of thinking/sensing and feeling/intuiting.

We have plenty of rationality and science at our disposal, but where do we turn to re-discover the power of the imaginal and its profound meanings? It was C.G. Jung who showed us that alchemy is a storehouse of the imaginal in which lie the deepest treasures of healing and reconnection for our culture. In alchemy, the Sun - the masculine - represents intellect with its emphasis on quantities whilst the Moon represents the feminine with an emphasis on qualities accessed via intuition and feeling.

We need to reunite those old opposites – science and alchemy – to help heal ourselves and the world. A powerful archetypal image that helps us do this is the Tree of Life, which features in many alchemical images such as this illustration from the seventeenth century:

Here we see two philosopher-alchemists, Senior and Adolphus, conversing by the Tree of Life. Between them is a downward pointing triangle, with the symbol for Sulphur on the left beside Senior and the one for Salt to the right beside Adolphus. The symbol for Mercury emerges between them pointing down to the Tree’s roots plunging into the Earth.

Senior and Adolphus engage in a lively debate by the trunk of the Tree. Senior has the Sun behind him and sulphurous words tumble out of his mouth. He holds an axe with which he could easily cut down the Tree with his solar intellect in the service of science and technology. Adolphus defends the Tree by pointing to its living qualities and intrinsic value. The Moon behind Adolphus imbues him with the mysterious salty spirit of the wide ocean with its lunar knowledge of dreams and the deepest recesses of psyche with which he balances Senior’s intellectual attitude.

The fruits of the Tree, emerging from the talk between the two philosophers (hence the upward pointing triangle), take the form of five stars, each of which holds the sign of a planet: Venus and Mars above Senior and Saturn and Jupiter above Adolphus. The highest fruit of all at the centre and top of the Tree holds the symbol of Mercury.

Together with Sun and Moon, we have the seven alchemical planets which symbolise the union of science and the imaginal. Why so? Because in Gaia Alchemy each planet offers us perspectives into an aspect of our Earth’s (Gaia’s) functioning as revealed by science whilst simultaneously opening up psychological vistas in ourselves which mysteriously cohere with the corresponding aspects of our planetary ecology.

So let’s go on a brief Gaian-alchemical excursion through the planets which we’ll imagine as metallic fruits growing on the Tree. Sun represents conjunction – the coming together of separated aspects of life. In Gaia these were pre-life molecules that eventually managed to conjoin themselves into the first living cells some 4,000 million years ago as well as all the complex relationships between species that knit themselves into resilient ecosystems. Inwardly we experience Sun as the wholeness that comes upon us when reason reunites with the ability to perceive Gaian scientific findings as images full of deep meaning.

Mars is the power of separation –that which pulls things apart so that they may be reconfigured into new forms. In Gaia these are moments of mass extinction or ecological reconfiguration. Separation appears in the geological realm when plate tectonics push continents and raise land masses above the seas, whilst within us separation is needed to discern and discriminate between the many opposing tendencies that struggle for dominance so that we can see beyond them.

Venus represents the arts of fermentation, which, in part, refer to the myriads of microbes as they break down, recycle and reconstitute the chemical elements of life – the same processes that gift us alcoholic spirits and bread as bi-products. We ferment inwardly when our previous psychological material rots down, leaving us free at last to experience our first glimpses of Gaia’s astonishing magnificence, vast as spirit itself.

Mercury, the topmost fruit on the crown of the Tree, represents distillation which in the realm of ecology relates to the ways in which ecosystems refine their functions into ever more complex and effective networks of relationships amongst species and with the rocks, atmosphere and waters that surround them. On a Gaian level distillation gives rise to emergent self-regulation of key planetary parameters such as global temperature and the distribution of key elements. Likewise, our psychological distillation takes place when new networks of beneficial inward energies coalesce and conjoin, connecting us with the deeply mysterious ever-shifting active intelligence at the very heart of life and matter, bringing us an enduring sense of happiness and well-being. Notice how Mercury points down into the Earth at the base of the Tree – showing us that this intelligence dwells deep down in the very roots of matter and the unconscious.

Saturn represents calcination – the intense heating of a substance until it is reduced to ash. In Gaia one thinks of a primordial ball of roiling molten rock that was our planet soon after it first appeared out of small rocky pebbles orbiting the sun some 4,600 million years ago. In this image, ash is the planet as a freshly-cooled solid ball of lifeless rock. A plate of sea-floor rock subducting and melting under a continent undergoes calcination, as does today’s Gaia as we heat her up with our greenhouse gasses. Saturn is active in us when we melt down the lead of ego in the heat of a sustained inner quest for a richer, deeper experience of life. Our futile efforts to bolster our ego are heated and reduced to ash – to our humblest and simplest of attitudes - as we await the next phase.

From Basile Valentin's 'L'Azoth des Philosophes,' Paris, France, 1659.

Jupiter represents dissolution - the dissolving of what was once solid into components liquefied by the waters of life. Here we have the chemical weathering of rocks on Gaia’s surface by rainfall that in time washes entire mountains and continents into the vastness of the ocean. In us dissolution happens when we dissolve the ashes of our everyday mental constructs into the world of dream and image, bringing deeper realms of psyche into the light of our conscious awareness.

Finally we come to coagulation, to the Moon. This is where the human psyche melds with Gaia’s physicality as revealed by the modern sciences of the Earth. We coagulate into Gaia’s living body and become active as plain members of her biosphere for the benefit of all her beings, including humans.

One can contemplate each fruit of the Tree as a flowing together of science and image. Somehow, we discern the subtle parallels between our own inner calcination and what happens to huge slabs of sea floor rock as they are pushed down and melted beneath a continent. In such moments Gaia comes alive.

There are a myriad more such ways in which the alchemical Tree of Life can help to connect us with Gaia, for these subtle meanings are inexhaustible. By contemplating the science of Gaia and alchemical images simultaneously, we can experience ourselves at times growing ever more deeply into the living body of our planet and of the cosmos that embeds her. It’s a journey full of wonder, full of healing, rich with discovery.

Dr Stephan Harding. Deep Ecology Research Fellow and Senior Lecturer in Holistic Science, Schumacher College, Dartington.

He is author of Animate Earth: Science, Intuition and Gaia, and editor of Grow Small, Think Beautiful. Ideas for a Sustainable world from Schumacher College. His forthcoming book is Gaia Alchemy.

“The astral currents created by the imagination of the Macrocosmos act upon the Microcosmos, and produce certain states in the latter, and likewise the astral currents produced by the imagination and will of man produce certain states in external nature, and these currents may reach far, because the power of the imagination reaches as far as thought can go. The physiological processes taking place in the body of living beings are caused by their astral currents, and the physiological and meteorological processes taking place in the great organism of Nature are caused by the astral currents of Nature as a whole. The astral currents of either act upon the other, either consciously or unconsciously, and if this fact is properly understood, it will cease to appear incredible that the mind of man may produce changes in the universal mind, which may cause changes in the atmosphere, winds and rainstorms, hail, and lightning, or that evil may be changed into good by the power of faith. Heaven is a field into which the imagination of man throws the seeds. Nature is an artist that develops the seeds, and what is caused by Nature may be imitated by Art.”

—Paracelsus, De Sagis et eorum Operibus

Linder

Earlier this year, Linder and Dr. Donn Brennan discussed the ancient Indian science of life Ayurveda – the benefits to health and wellbeing it can offer as we move into Autumn, as our bodies and minds adapt to life with the pandemic, and what it can teach us about the limits of our own world view, particularly with regard to healing the energetic field of the body. Dr. Brennan is an Ayurvedic healer, the founding President of the Ayurvedic Practitioners Association in the United Kingdom and one of the first western medical doctors to train in India in Maharishi's Vedic Approach to Health. British artist Linder created a new series of work exhibited in The Botanical Mind, which examines and re-imagines the incest motif in Ovid’s Myrrha myth. Myrrha makes love to her father, metamorphoses into a tree, and gives birth to Adonis from her trunk. The aromatic of resin myrrh is thought to be the tears she wept in remorse.

Myrrha, being transformed into the myrrh tree, gives birth to Adonis. Engraving by M. Faulte, 17th century

Donn Brennan (DB): Tell me about the project – The Botanical Mind…

Gina Buenfeld (GB): I suppose one way of thinking about it is that it foregrounds the mind as a principle running through all aspects of the living world, to reappraise and reevaluate our relationship with plants. It builds from the understanding that non-human entities have an energetic life force. It really started for me when I first went out to the Amazon – about five years ago – and encountered the way that indigenous peoples there really understand plants and the forests that they live with. And to me, that felt so much more elemental than how we understand it here. The plant kingdom out there is so primary, immersive, it’s not a collection of isolated plant specimens, but it was really like this element that people and other animals live in and through like the air or the water, or fire, you know, it’s at the foundation of life. So I became really fascinated with that and their spiritual understanding of plants – the way they can communicate and work with plants for healing is really based in their spirituality, it's kind of at the core of their whole cosmology really. I felt motivated then to think about how we ended up where we are in Europe, having this very mechanistic and chemically-based understanding of plants, thinking in terms of what they can do to the physical body without understanding the energetic body, and how that heals. I started looking back at practices that existed before the scientific revolution, and before the Enlightenment, before spirit and matter were split apart in our forms of knowledge. And so a lot of the exhibition draws on medieval ideas, or earlier, from antiquity, and looks at more marginalised scientific ideas that have continued to exist but that are by no means in the mainstream here. So to me, Ayurveda is really important and fascinating.

DB: Ayurveda is profoundly underpinning everything that you're doing. The understanding in Ayurveda would be absolutely supportive. It's total wisdom, the perspective you're taking, in comparison to the reality of loss of memory of our culture. It's an awakening. It's a lovely concept that you actually use the exhibition to awaken people to their own innate wisdom and the consequent connection they have with life around them, which co-exists with the same laws of nature.

GB: That’s our hope. One of the things that has interested me in terms of our European heritage is humoural theory and my understanding is that the Ayurvedic system is much older than the European model.

DB: The European model would have originated from the ancient Greeks, where they had phlegmatic and choleric. Alexander the Great conquered many lands and came to India where he was quite fascinated by the culture and actually had Ayurvedic physicians within his court. And so, those humours are absolutely the reflection of the Ayurvedic principals which are the five elements, bound to the five senses - a way of explaining how we create our reality through our senses and create varying qualities of relationships with everything around us - which is simplified to the three fundamental dynamics of Vata, Pitta and Kapha. These different humours are qualities that need to be balanced, within and with the universe around us, to awaken and integrate ourselves with life and live a fulfilled, happy and wise life. Ayurveda has been seeding for millennia. Even the pulse diagnosis and acupuncture points in traditional Chinese medicine derive from marma points in India that travelled East with the Buddhists. Ayurveda goes back beyond that - way, way, back.

How old is Ayurveda? Well, it is as old as life because when you create your own structure, there's an intelligence there and as long as there was life, there was that wisdom, that deep knowledge. That's Ayurveda, it’s the knowledge of life.

Linder (L): Do you still refer within your practice to the ancient texts of Ayurveda?

DB: The textbooks we use must be about 2500 years old, but they're just rewritten versions of even older texts, stretching back to the civilisations in the Himalayas during the Mohenja-dara era. Those cities were the most ancient, maybe 7000 years old – the greatest cities of their time. All of the training of any Ayurvedic practitioner will be in the principles that are described in the old texts. The old texts are considered the standard, in that in the same way we would use scientific researchers establishing truth and standards, Ayurveda would recognise that which has survived the test of time is the ultimate truth. Because even a medicine like aspirin, 100 years after its discovery, has been discovered to create Raye’s syndrome in a very small proportion of very tiny children. We keep making discoveries in time. So the most ancient principles and practices described in the oldest texts are the time-proven basis of the Ayurvedic practice, which is so profoundly flexible, that we can adjust those principles to the time we live in.

The Susruta-Samhita or Sahottara-Tantra (A Treatise on Ayurvedic Medicine). Nepal, Text: 12th-13th century; Images: 18th-19th century. Ink and opaque watercolor on palm leaf

L: Can you describe the role of the plant within Ayurveda?

DB: The plant is so important! I was blessed with a mentor; he was absolutely famous in India for his knowledge of plants. He hadn't taken any traditional Ayurveda training, but had met an old sadhu, a wise old man, and spent 30 years walking the Himalayas with him telling him everything about the plants they met along the way. He had a working knowledge of some 6,000 plants and he could stand in a field and know a plant from its fragrance, from its taste, from its qualities. And then he would suddenly tell you everything about the plant including the Latin name and family and the properties and the uses of it.

He was so sensitive to plants and he would say that the plant kingdom wants now to help us to regain our health. It’s a fascinating way of thinking about it, a plant is a living being and being a living being it is an aspect or expression of the same fundamental field of life which is consciousness and awareness. It has its intelligence and life structures, according to the same laws of nature that are in my physiology as well as in the plant. So, the plant actually comes to me when I imbibe it, as a reminder, that its intelligence is realigning and awakening and enhancing my memory of natural function, where I have distorted and disturbed myself through improper lifestyle and routine, throwing my system out of balance. The expression of my DNA becomes confused - the proteins and enzymes are distorted because the underlying intelligence within that DNA is turning on the wrong genes. But then the plant comes along and we imbibe it and suddenly the switches are tuned and turn on the right genes, the intelligence is restored, the body remembers. Now the healing, the recreating of the wholeness, which had been lost, starts to happen.

The plants are working by their antioxidant and anti-inflammatory chemicals on one level but that level is just the gross objective material that we are thinking about. In truth, that's based on a finer level – in the organising principles, which is the intelligence in Nature, which is the same intelligence in my nature, and the plant is awakening that. Fundamentally, that plant is life, it's alive and I'm life, I'm alive, so it gives me that quality of enlivenment as well, operating on all these different levels. We’re so caught up with and obsessed by the material form that we cannot deeply appreciate the far more refined and holistic and fundamental perspective that Ayurveda brings about.

L: Can you talk about a couple of the most popular plants in Ayurvedic medicine?

D: Ashwagandha is a wonderful herb, the best tonic for a man's body. It integrates the nervous system, it’s the best anti-stress tonic and it's also good for strengthening the body. Shatavari is a wonderful, beautiful, green luminescent plant with innumerable roots, like long carrots that are the best tonic for a woman's body at every point in her life, giving her nourishment. Again, not merely on the physical side, but as a tonic for the mind as well.

There’s a mineral pitch, ‘shilajit’, that emerges from cracks in the Himalayas that is the transformed substance of ancient forests that were crushed by the collapsing mountain. And they're just there, within the actual depth of the rocks giving out this mineral pitch, that's really good for clearing toxins and for diabetes. So, there's amazing use of minerals and all aspects of the herbs, the root, the flower, the seed in Ayurveda that has the richest knowledge of plants out of all the traditions. And it combines this with great strategies of cleansing – including the capacity for the body to cleanse itself and clear the debris it’s collected on the way.

But I think the real essence of Ayurveda is its capacity to take us from this material level and to understand how, through the senses, we've created five ‘bundles’ of energies, called elements (space, air, fire, water and earth). They create physical form. The senses are those channels through which awareness or consciousness flows. Ayurveda then reconnects us through these five elements, through these five senses, back to their source. The source is that one who hears the thought or feels the emotion. That’s Ayurveda’s uniqueness, to operate from that field, that source, through all its levels of feeling and intellect and thinking and how balancing – even when just in the material form - allows the feelings to be enhanced, the thinking to be clear.

Shatavari / Asparagus racemosus

L: Are all the plants that are listed in the most ancient texts still available or have we lost some now?

DB: Fortunately, India being a very traditional place, this knowledge is passed down in families one generation to the other, and the vast majority of described plants are recognised even nowadays. However, there are some that there is confusion with: is it this plant or is it that one? There is indeed talk of the most sublime plant of all, soma, in the Himalayas somewhere and just to take that would be of the ultimate transformative value. That's mythical, because we don't really know which plant that is anymore - that’s life!

L: There's much speculation about soma, isn’t there?

DB: Absolutely and of course that’s partly what makes it a very rich tradition I suppose - to have these unknowns as well. When we are awake - because we are so far from awake to our full potential - when some quality of human awareness, our collective humanity, is awake, through enough people waking up, then we may cognise what soma was, then we may know the plant.

L: Can you say something about the three doshas - vata, pitta and kapha - in Ayurveda?

DB: It's very simple, because that's the beauty of Ayurveda, to make it simple. We're all unique, and we all have absolute qualities. But we're all fundamentally from the same source - one foundational source at a very deep level - giving rise to infinite possibilities and expressions through three fundamental processes. So when you, as the silent witness, the one who has your thoughts and experiences, begin to create, construct - really become your body there at that depth - there's that primary movement of consciousness. That’s called vata, the process of movement.

Then you start to transform that consciousness into your feelings, your thoughts, your structure, everything in mind body is transforming, transforming, transforming. That's pitta, the second of the fundamental dynamics.

Then all the innumerable movements and all the transformations are integrated into the structure by a cohesive quality. This glue is called kapha. We are each composed of these three dynamics - all of us are vata, pitta and kapha - but everyone is unique in their proportions. Vata people are very light, quick, moving, cold, dry, so vata is very light and they’re thin and light, enthusiastic, vibrant, refined, artistic, creative. There's a lightness about vata – they’re fast, they pick up information but they forget it, they rush, you know, they're very light, quick-moving, they’re always on the go and so these are qualities of vata that are more seen in that sort of a person.

Pitta is the process of transformation and Pitta people are very intellectual and analytical, highly motivated, driven, perfectionist, precise, orderly, and of moderate build strength and stamina. They have a lot of fire in their heart (passion for life) in their gut (for food) - they love food, they’re great chefs.

Then there's kapha - kaphas can't be bothered either way. You know, they're very easy going, slow - thinking slowly, moving slowly, slow to pick up information but they never forget. And very strong and grounded, practical. If that kapha person sits at home eating cream cakes, having the quality of a heavy, slow lifestyle, they end up being excessively kapha – too heavy – they can put on weight, develop a depressed mood and a heavy heart. Then they start getting heavy heads, sinusitis, which is kapha out of balance. All they need is to get a bit of exercise, eat a bit lighter, get up early in the morning and in this way by balancing their kapha, they can lift their mood and their weight can begin to stabilise.

On the other side of the coin is if someone is vata and starts to take more exercise and to get up earlier in the morning, well, they're already very light and quick so they start to get more excited and can become anxious or panicky. They need to eat the cream cakes more - it’s different strokes for different folks!

L: The art world can be very vata!

Ayurvedic Man, c. 1800. Gouache with pen and ink painting

DB: Absolutely! The reason for that though is because our gross senses of taste and smell are more attuned to the material elements, and kapha is more attuned to these senses. The intellect is much more the sense of sight – insight – and this is Pitta’s strength. Touch, feeling and hearing these are the subtler senses to do with the air and space elements and this is more vata.

We evolve from the unbounded, immortal being through these dynamic processes: movement of air and space; then the friction of fire comes up; then the fluidity of water; and then the solidity of earth. Of these fundamental elements in our physical structure the subtlest – air and space – are appreciated through touch and hearing. Artistic people are operating in those more refined senses, that’s why they’re more vata because those are the senses of vata. Touch on a sublime level is fine feeling and intuition.

L: As we go into autumn, amidst daily warnings from the media about the coronavirus with its language of “the unseen enemy”, how would you recommend that people prepare physically and emotionally?

DB: First, just recognise that the medical paradigm is defined in formulating a problem and then attacking that problem - whether that’s “killing” bacteria, the virus or cancer cells, it’s very, very awesomely fearsome, it’s about battle. None of us should take that perspective except the doctors, let the doctors be the experts in that and let the rest of us focus on health, healing and strength - now that’s what’s been missing in the media. That’s what’s disturbing too, our whole civilisation, particularly the vulnerable, naturally are fearful with all of that going on.

We should be focused on our health, our creative health, and that will be an antidote to the negative publicity and would also put our immune systems in a more resilient state to be able to deal with the virus. Actually, coronavirus is causing kapha problems for people whose kapha is out of balance, whether they’re overweight or diabetic or have heart conditions. The people who die unfortunately have a bad kapha imbalance and this coronavirus is a kapha problem. If we know how to balance kapha by adding a couple of spices to our diet and getting some exercise and other simple strategies, then we can improve our immunity and in that sense protect ourselves, as we also continue to wash hands and social distance as needed.

Going into autumn is a vata season - the sun is fading away and the nights are becoming darker. In ancient times people actually slept more because what else could they do in the dark? We should be taking more rest in the autumn, taking life easier, we should be more meditative and we should eat more nourishing foods to balance the qualities of vata that come up at this time. We should understand that our nature changes with the seasons, the seasons happen within us and we should make appropriate adjustments. In the summer, we intuitively and spontaneously know this - we want leafy green salads, fruits and juices, everything that balances the heat of pitta. But in the autumn, after the harvest festival, we should be going into a rest mode so that we don’t strain, rush or hurry in the autumn and then remain happy and healthy through the winter. But because people go back to school, struggle and take on new projects, they then hate the winter because they’re exhausted!

L: Listening to you talk about time, within Ayurveda does time become our laboratory? And when we take certain herbs do our bodies in turn become the laboratories in which we're assessing – within time – how the herbs affect us?

DB: Wonderful question Linder, because you've taken this now beyond time. Because the fundamental, most profound reality of Linder Sterling, and of everyone who might listen, is that you're not your physical structure existing in time. You are not your thoughts and feelings which come and go in time. You were two years old and you were 20 years old and you now still are Linder Sterling, and yet your body constantly renews - in every three years the last atom is replaced - and your mind has definitely changed over that time. You are not your mind, you are not your body, you are that Being, that Awareness, that Consciousness, that profound essence of life, which is just Pure Awareness. That's our fundamental reality and that is beyond time. That is a field of immense potentiality from which everything arises, our thoughts, our intelligence, our creativity, our art, our music - they actually are refined ways of re-integrating us. As we listen to music or look at art through the senses, we regain some coherent, integrated style of functioning to cognise a reality which is far deeper, which is our essence, which connects us. Every one of us has Consciousness and in truth in Ayurveda, that field of being of Consciousness is the same field which structures life, structures the whole universe. The whole universe is that field of Awareness or Consciousness manifesting manifold worlds, perhaps universes, certainly galaxies, certainly this planet, certainly the rain forest, certainly our physiology.

The very same intelligence - that innate being, those laws of nature or principles of organisation, whatever you want to call them - that is structuring your physiology, Linder Sterling, are the same dynamics and organising principles, that are structuring the entire universe around you, including all the plants, including myrrh.

All is product, the production of a vast field of Awareness or Consciousness, of which we are the culmination, which allows that field to appreciate itself through our awareness of the whole.

Unfortunately, in the process, we've lost our memory and we've projected ourselves out to a very materialistic perspective now, which we live in – a universe of material that has to be analysed in terms of its bits. In that process we lose the underlying wholeness in our awareness. It is still there, but it is no longer in our awareness. We got lost; we lost ourselves, the witness to the experience, as we projected into all our perceptions. Who's the one who’s perceiving? Who's the sublime? Who's the divine? Who's the one who knows? That we need to wake up to and that we do to some extent through art, music, beauty. Wordsworth wrote “that serene and blessed mood, in which the affections gently lead us on, until, the breath of this corporeal frame and even the motion of our human blood, almost suspended, we are laid asleep in body and become a living soul.” That’s an experience in poetry that reminds us who we are. With awe we can awaken to our higher reality.

L: Even as you're talking, I can feel my consciousness transcending.

DB: Wonderful, wonderful, wonderful, because you are awareness, Linder, and all of us have been trained in this mad world by educational systems that become obsessed with endless fact gathering. We have been trained to put our attention out there, so all we can attend to, is what becomes our life. And now, when we actually start to attend to a finer reality of subtler levels of mind, finer essences of feeling and begin through that attention to awaken that field within – yes, we feel ourselves waking up. And at this time, that’s so vital. Because if we don't wake up now, we will have destroyed the planet through global warming, we will have destroyed ourselves and future generations.

So it's no longer a choice, we have to wake up now, so that we find the wisdom to reintegrate with nature, and allow nature to flourish in us and in our surroundings, with joy, happiness, and fulfillment. That’s the necessity for us to go within.

Ayurveda is Veda – Consciousness – plus Ayus, meaning lifespan. You're talking about time? So, Ayurveda is the wisdom, knowledge and expression of our potential in this lifespan, in this time – to take the unbounded, immortal, eternal being into this material, mortal, minimum lifespan of a mere hundred years. So that we can use this hundred years to wake up to this immense potential available within us!

L: In the works that I’ve made for The Botanical Mind I refer to myrrh, which we know predominantly as one of the gifts given by the three wise men to the infant Jesus. Is myrrh used in Ayurveda and which properties is it seen to have?

Hieronymous Bosch, The Adoration of the Magi, c 1475. Oil and gold on oak

D: Myrrh is very interesting. Of course gold was given as a symbol of kingship and an offering of wealth. Frankincense was given as a symbol of spirituality and myrrh was given because myrrh was considered in a sense a panacea, it was so good for so many different health conditions. Myrrh was like an offering of health – that would have been its position. Commiphora myrrh and there’s another tree commiphora mukal and they’re very close. Commiphora myrrh you find as a tree more commonly in the Middle East and in Africa, Commiphora mukal is more common in India. In India, both are used, it’s the gum from this tree that is the myrrh and it has a very important role to play in Ayurveda because it not only has its own properties but it’s often used in combinations, in many combinations you get commiphora. Its properties are to balance vata, which is very fundamental and moves everything in mind and body, plus commiphora balances kapha. Myrrh also removes obstructions, so it’s a very predominant preparation in the treatment of pain, arthritis, neuralgia, and aches and pains in the body. In fact there was myrrh in the wine offered to Jesus on the cross, which was traditional for crucifixion, as it had properties to ease the pain. In Ayurveda, myrrh is also useful for chest problems, for coughs and colds, and for women’s problems too. There would be very many different beneficial effects from the plant. Why medicine would have such difficulty coping with it is because in medicine you have one chemical for one purpose, whereas plants have innumerable chemicals that are synergised in our physiology and have an unbelievably complex effect that medicine could never fathom because there’s so much going on to create all these different effects in the body.

And then again, modern research comes along and says that myrrh is antiseptic, antioxidant, analgesic, antimicrobial, anti-fungal, anti-inflammatory, it’s anti-carcinogenic, it’s anti-hyperglycaemic, it’s chemo-protective, it’s hepatic-protective. So, there were medicines coming along that would have had these effects, maybe we can now begin to comprehend how myrrh could be used as a panacea.

L: I’ve been having very intimate conversations with myrrh for a few years now and I feel very familiar with its various properties and its effects upon body and mind. I find that, just as sometimes I think that I must have some tea, that I now know when I must inhale myrrh or massage myself with a myrrh oil blend.

D: It’s interesting because that would have been the original science behind the discovery. The science would once have been that when the mind was stabilised at the base, from that silent unchanging basis, people could cognise the full effect on every level of feelings and thinking and physical being. There would have been an immense sensitivity that they could fathom how to combine 40 different plants and know that the synergy was going to be so effective to prevent ageing or some other effect.

And this is what you’re describing to the n-th degree, and that’s not anti-scientific. The whole basis of our science is mathematics which is a mental exercise. We recognise the laws of nature within and without through mathematical formulations which we project into the universe, that underlie the complexity of quantum field theories and the whole basis of science, and it’s the same way of knowing about myrrh. We’re moving out of the dualistic notion of mind or body and we’re recognising that our mind is our body, our body is our mind. We are consciousness.

L: That’s a very beautiful point at which to complete our conversation. Is there anything you’d like to add?

D: Here’s wishing that through this wonderful display of beauty in The Botanical Mind that everybody is awakened to their sublime and joyful being and that they may all go in happiness and health and wellbeing.

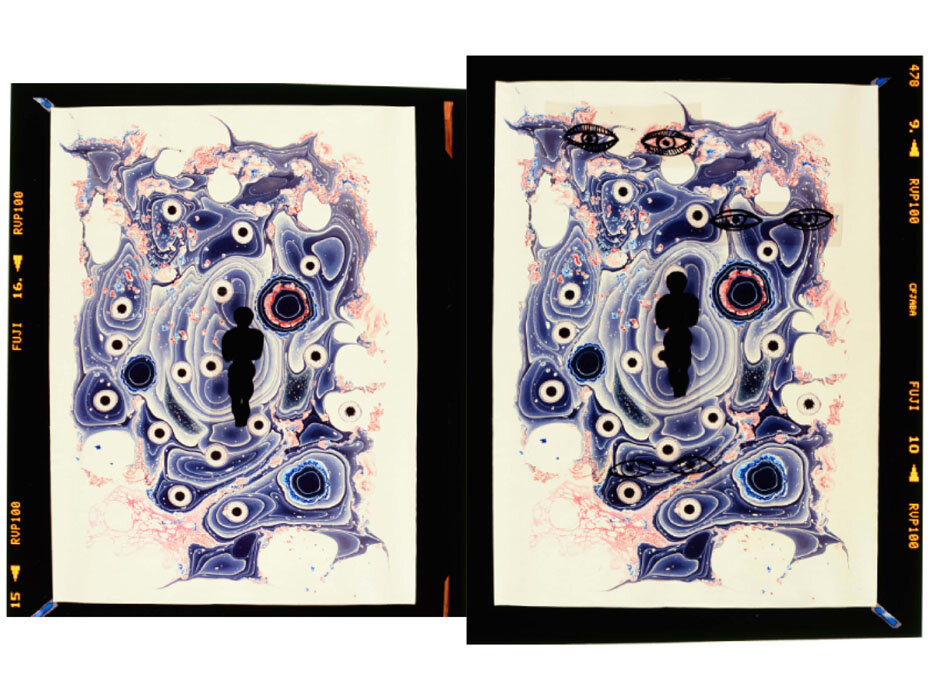

Linder, Myrrha Mutatae, 2020. Photomontage

Ithell Colquhoun

Ithell Colquhoun (b. 1906, India) was a British artist and occultist. She studied at the Slade in the late 1920s and was later a member of the British Surrealist Group, exhibiting with Roland Penrose at the Mayor Gallery, London in 1939. She was expelled soon after, her work and ideas apparently too esoteric, even for them. She moved to Cornwall shortly after where she lived and worked until her death in 1988.

As well as her work as an artist, she wrote a number of books and articles on magic, divination, landscape, and myth, as well as stories and poems, including: Children of the Mantic Stain, 1952; The Living Stones: Cornwall, 1957; Goose of Hermogenes, 1961; Grimoire Of The Entangled Thicket, 1973; and Sword Of Wisdom - MacGregor Mathers and the Golden Dawn, 1975.

Colquhoun was a practicing occultist, interested in various systems of magical thought, hermeticism and alchemy. She created a tarot from shapes and forms automatically produced through poured enamel paints, as well as making paintings and drawings based on various automatic, or ‘mantic’ techniques. These works sought a kind of equivalence with the patterns and forms of nature and were, for her, aids to divination, enlightenment and knowledge.

“Vegetation is under the sway of elemental Water and the West, so it is fitting that Tree-Alphabets should come from the Celtic fringe. Were they brought, like the Cauldron of Abundance itself, from the submerged city of Murias? In their ancient and essentially poetic system, the name of each letter is also the name of a tree or plant, linked through the flow of its inner sap to a month of the lunar year…

It may be significant that in 1971 I made a number of drawings based on the automatic process known as decalcomania, which evoke the spirit of various trees – Beech, Rowan, Ash, Willow, Oak, Vine, and Silver Fir. Some of these, and the poetic sequence, I offer to the White Goddess at a time when wasteful technology is threatening the plant-life (and with it all organic life) of earth and the waters.”

From the Author’s Foreword of Grimoire of the Entangled Thicket, 1973. First published by Ore Publication, Hertfordshire.

Ithell Colquhoun, The Dance of the Nine Opals, 1942. Oil on canvas, 51 x 69 cm. The Sherwin Collection, Leeds, UK / Bridgeman Images

Ithell Colquhoun, A Visitation 1, 1945. Oil on canvas, 61.5 x 51 cm. Courtesy the estate of the artist

Ithell Colquhoun, Tree Anatomy, 1942. Oil on wood panel, 56.9 x 29 cm. The Sherwin Collection, Leeds, UK / Bridgeman Images

Ithell Colquhoun’s Extra Dimensional Consciousness

Amy Hale

Amy Hale is a scholar of occult, esoteric and marginal cultures. Her research and writing ranges from folklore and mythology, to modern Pagan and occult subcultures in United States and the United Kingdom.

In this essay, she has adapted material from her forthcoming title Genius of the Fern Loved Gully: Ithell Colquhoun Artist and Occultist, Strange Attractor Press 2020.

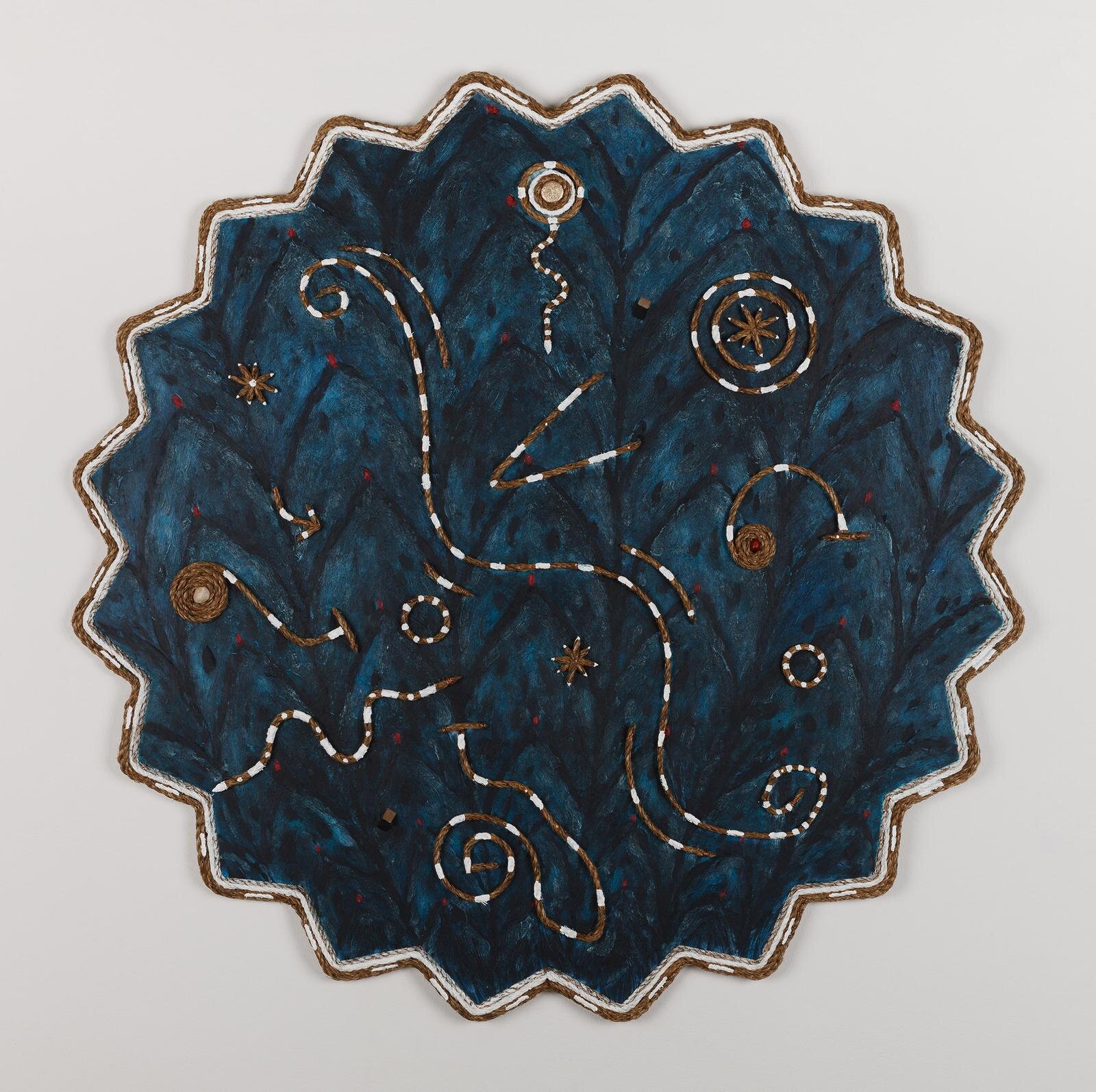

Daniel Rios Rodriguez

Daniel Rios Rodriguez studied at the Art Institute of Chicago and at Yale, before returning to his hometown of San Antonio, where he now lives. His small, densely-impastoed icon-like paintings are inspired by the Texas landscape, often through the lens of American folk art: paintings of birds, rivers, flora and fauna are embellished with found elements (dried ears of wheat, fragments of rock, feathers or seashells), which he incorporates into the textured surfaces. Rios Rodriguez has a longstanding interest in what he calls “essential forms” — the spiral and the snake — exploring these enduring archetypes in relation to the immediate landscape around him.

Nyctanassa, 2018

Oil nails, rope, wood, aluminium, acrylic, river stone, Texas mountain laurel bean on wood panel

“This painting represents for me a nocturnal perspective of both the plant and animal life of the natural world. They are inseparable. There is something to the spacing of each piece of rope, each representing a natural life form, that mimics how we are currently navigating our social interactions. It seems to me that we are now navigating our days as we would navigate the night in a strange and new city. Like constellations, like animals, like plant life itself we are spaced apart and wary of each other. But we know there is life in it. Each root needs its own well and sunbeam. Each Star its own gravitational pull on orbiting masses, each animal its own shelter and kin. Yet somehow we also recognise we form a whole world of meaning. That life, despite all attempts to hinder it, will persist. It is infinite. That there are more stars, birds and flowers yet to be born. We grow on top of and push and pull at each other in order to live, in order for others to live so that we can all experience the night again and again.”

Daniel Rios Rodriguez

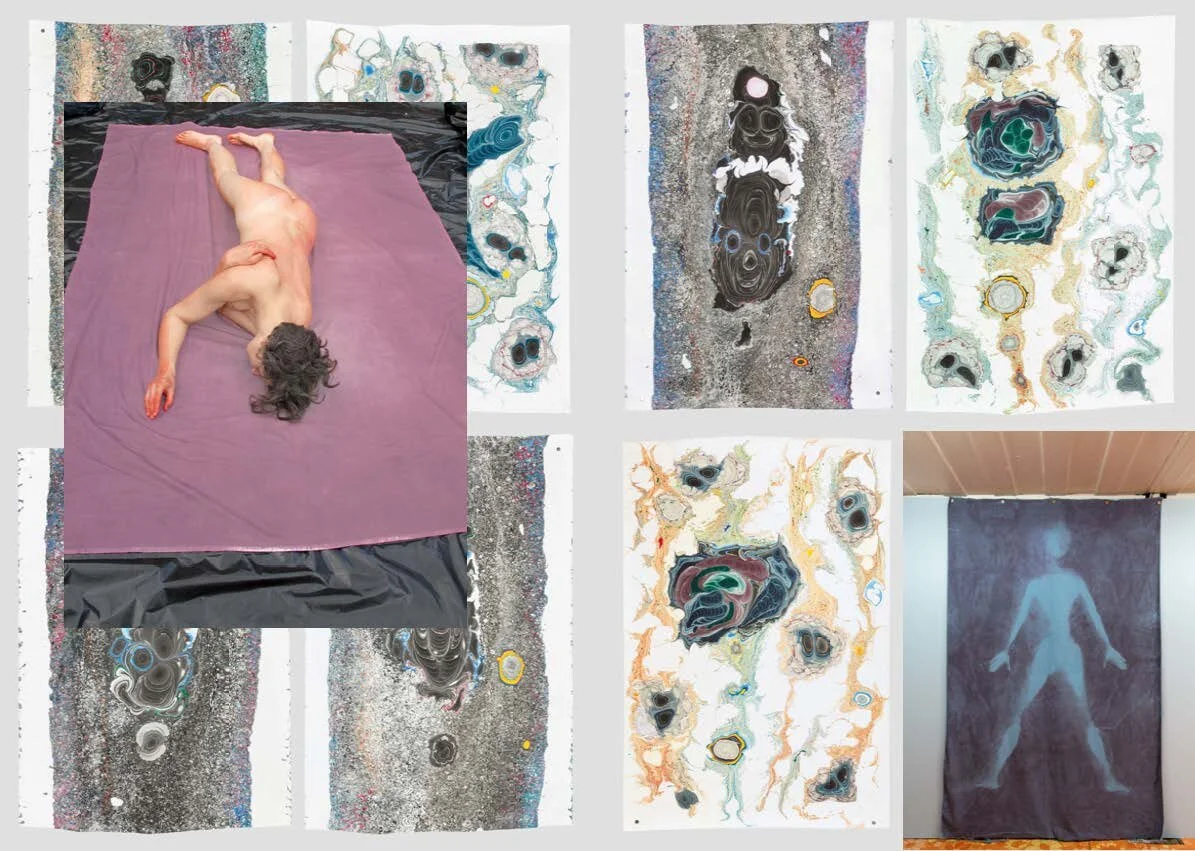

Kerstin Brätsch

Kerstin Brätsch’s practice has involved collaborations with other artists, astrologers, psychics and artisans working with traditional stained glass and paper marbling techniques. Her distinctive, highly saturated and abstract images resemble patterns found in nature – geodes or other stone formations, or the markings of plants and animals – and also read like ciphers, a kind of language.

She works with processes that are like alchemical rituals, combining pigments and liquids with other materials in precise measures according to traditional, event ancient, methods and surrendering to the intelligence of the materials in themselves - the way they behave.

'“I like to place painting in an extended field to draw out its relation towards the body (be it physical, psychic, psychological or social). I consider painting as an ever-becoming body, and my journey through different mediums is done to view painting from different angles.”

Kerstin Brätsch

Kerstin Brätsch, Unstable Talismanic Rendering _Schrättel (with gratitude to master marbler Dirk Lange), 2017 Pigment, watercolour, ink and solvent on paper; 274.3 x 182.9 cm. Photo: Kirsten Kilponen; Courtesy Gavin Brown's enterprise

“Marbling as a kind of cookery appeals and belongs to the whole ancient tradition of secrets, inherited and encapsulated in hermeticism, including glassmaking, colours, medicines, alchemy, perfumes, artificial gems, strange geology and botany, silk, hallucinogens and poisons—recipes of all sorts. Paracelsus collected such secrets from miners, old women, apothecaries, and the like.”

Peter Lamborn Wilson

Kerstin Brätsch in conversation with

Gina Buenfeld

Ahead of The Botanical Mind: Art, Mysticism and The Cosmic Tree, co-curator Gina Buenfeld visited artist Kerstin Brätsch in the studio she shares with traditional artisans a few streets from the river Tiber in Rome. For the last 18 months she has been collaborating with the artisan Walter Cipriani, a plaster specialist and decorative painter. In a café close to Kerstin’s studio in the Trastevere district they discuss the new work Kerstin is developing and many other shared interests.

First published for Luncheon Magazine, no. 9

Gina Buenfeld: Time feels really important to your studio processes – the different registers of it in the new work you’re making, their immediacy as images but also a slower time accreted through the labour of making them, in the transformation of the material.

Kerstin Braetsch The new body of work is made using stucco, a form of plaster originally used in the 17th century to imitate marble and other rare stones. They’re easily mistaken for stone formations unless you touch them and realise they’re room temperature. Stones are formed over centuries by invisible forces – chemical reactions inside the earth, off-gassing and so on – which lends them their beauty, and I was interested in simulating the same ageing process using modest means. The process of making the Stuccos is incredibly technical and labour-intensive: sanding, repeated stuccatura (filling in air holes with pigment), polishing and finally waxing, which together creates the reflective surface akin to stone. The creation of the works is like an alchemical ritual: the mixing of the pigments in a specific manner, and the plaster material formed with precision following an ancient knowledge that is almost forgotten. It’s a fascinating process whereby, using just water and powder, the material slowly starts to sediment into a solid. The works appear to store this time in their materiality, and I feel as if they grow into their own material. G I NA : You’re working with and amid so much history – in your studio, you’re surrounded by classical statues undergoing restoration, and using this technique that’s endured for hundreds of years. Despite all that tradition, it still feels like a place of experimentation. The shelves stacked with luminous powdered pigments – it was like a laboratory where you’re bringing this old aesthetic tradition into a contemporary vernacular.

Kerstin: The experience of making the work is psychedelic and messy. I like to think of the plaster pieces as breaking apart to form bones, body parts, ritualistic amulets that when placed together resemble ancient runes. The material looks as if a brushstroke – an action – has been trapped in the moment, like a fly enrobed in amber. The series Brushstroke Fossil for Christa (Stucco Marmo) is supposed to read like a language, and stenography, but also Internet vernacular and emojis. And in the related body of work Fossil Psychic for Christa (Stucco Marmo) I build and shape the stucco works into an image of a body, or an ‘image-corpus’ as I call it, an image of a corpse. From within, the works’ energy emerges, creating the appearance of a de-deadened material. As if something that didn’t have a body has returned to the physical world, fossilised in a new form. They could read as fossils of ghosts. With this intervention I’m looking to test the limits of this traditional technique and place it in dialogue with contemporary painting.

Gina: I’m interested in that alchemical idea of transmutation from immaterial to material.

Kerstin: I am too, and also in terms of the immaterial and material conditions of seeing. My work has transformed from transparency into opacity, from light sources to water and dust. Originally I was painting on Mylar in order to subject painting to a stress test through light. Painting is always asking to be placed in the right light (the inconceivable idea of the sun) and my impulse was to deconstruct that idea, to ‘destroy painting’, as Poussin says of Caravaggio and to expose it to a ‘bad light’. When I collaborated with UNITED BROTHERS (the artist Ei Arakawa and his brother Tomoo, who run a tanning salon in Fukushima, Japan).

I exposed my paintings to the artificial lights of a tanning salon (an imitation of sunlight). This exposed them like an X-ray, making visible every mistake (fingerprints, brushmarks and bristles), thereby revealing the vulnerability of the painting. Working with light in this manner eventually led me to glass, a material that only exists fully with light – without it, it’s just dead matter. And now I have picked up the dead matter and am animating it.

Gina: I think for many people alchemy evokes a proto- scientific kind of magic that’s about transforming one metal into another. But it’s much more expansive than that and involves a re-envisioning of matter and mind – thinking of them as intrinsically involved in manifesting the world. Some images have a potency that can affect the mind and body on a deep level, even bringing about transformations in consciousness. Jung was fascinated with mandalas – he painted his own and wrote about them as a universal form that speaks directly to the structure of consciousness. He also recovered a lot of early alchemical ideas and championed their relevance to the operation of the mind. There’s something in your process that seems to forge a coalition with the material and energetic qualities of what’s at hand – an alignment of mind (in the broadest sense) and material to bring something into existence.

Kerstin: I like to place painting in an extended field to draw out its relation towards the body (be it physical, psychic, psychological or social). I consider painting as an ever-becoming body, and my journey through multiple mediums is done to view painting from different angles. Each iteration of my work is informed

Kerstin Brätsch, Fossil Psychic for Christa (Stucco Marmo), 2018, plaster, pigments, glue, wax and oil on honeycomb, felt , 97 x 139 x 5 cm. Photo: Daniele Molajoli

Kerstin Brätsch, Work in progress, Fossil Psychic for Christa (Stucco Marmo), artist’s studio, Rome, 2018. Photo: Daniele Molajoli

by what preceded it and operates accumulatively, with the timeline of my overall oeuvre embedded in every new piece. To me my practice morphs in the way that cells reproduce in a human body. In a healthy body, cells are able to clone themselves exactly, but with age small errors and mutations start to occur, proliferating and creating different forms that the body is forced to confront. This fracturing is how I like to think about the mediums I work through, where a shared origin branches out into altered expressions of, essentially, a core idea.

Gina: In some of the more recent works you’ve started to integrate mosaic into the stucco. That intervention is really interesting – the stucco technique imitates stone, it has this mimetic behaviour that looks like marble or agate and so appears organic even though its hand-crafted, while mosaic, for me at least, is associated with the pictorial; it feels like deliberate intention is more explicitly at play there. How do the mediums and processes you’ve used, from painting on paper, to the Mylar paintings, the work in glass, marbling, stucco and mosaic, relate to the idea of mimesis and mimicry?

Kerstin: I was always struck by Rosalind Krauss’s discussion of mimicry as a form of psychosis, and how she relates it to the action of the mating rituals of the praying mantis. She describes how the female feeds on the brain of the male during sex and how the males often play dead to try and protect themselves from being beheaded, which happens anyway after the mating part is over. This example is extreme and graphic, but it gets to the point that mimesis is a strategy of survival.

While working in a glass workshop in Switzerland, I was given Sigmar Polke’s leftover sliced agate stones from his Grossmünster project in Zurich [Polke created windows made from slices of semi-precious stones in the Grossmünster church; 2009].

I incorporated his ‘trash’ into my work, allowing these elements to be the points around which content was arranged (stones as eyes, spines, lettering, digits, myth). I had the urge to go deeper into this gift and imitate the ‘brushwork’ of the stones themselves, which I consider paintings made by the earth’s core, a completely inaccessible life force. The only way I could imagine doing something like this was to radically distance myself from how I traditionally made a brushstroke – that is, with oil paint alone in my studio – and expand my practice to involve the hands of others and create something collectively induced.

During each of these experiences there occurs a magical shift where both of us, artist and craftsman, no longer know who we are. Our identities become interchangeable and we become something else, a third. The two hands of a craftsman combined with the two of an artist – we become a four-armed being. This is idealistic, but I believe moments like these provide a new perspective on familiar situations.

Gina: As if through a dissolution of the self, you assimilate to another form, or state of being perhaps? I think mimesis is programmed deep in the evolution of plants and animals – it dissolves the boundaries between the mineral, vegetal and animal kingdoms, if they were ever distinct in the first place, and makes them porous. Animals assimilate themselves to their surroundings with colour and pattern; they disguise themselves for protection or, conversely, use the same strategy to attract allies. There’s a species of snake that has evolved so that the tip of its tail looks so much like a flower that it lures migrating birds to their demise. Likewise, specific plants masquerade as insects – the bee orchid for example – to attract

pollinators. All flowers are just mutated leaves that deploy colour and pattern to communicate. Patterns operate in a preconscious, instinctual way to perpetuate life – encoded in an evolutionary principle, something that’s unfolding through us. This active function of pattern is at the core of The Botanical Mind, which delves into the mysterious world of plant intelligence, in part, through abstract painting. It’s exploring this reflexivity of vision, a reciprocity between the patterns of the external world and the interior horizon of consciousness.

The works you’ve made with marbling are also mimetic, imitating stone, and you’ve described that process – of dropping ink onto a liquid (algae) bath – as being one of surrender, the pigment to the liquid field, that gives rise to an emergent pattern. They resemble energy fields, auras, patterns that have similar configurations from the vast scale of the cosmos to the biological imaging of cell formation. This process in your work seems be a kind of tuning into and collaboration with – through – the material, its properties and behaviours.

Kerstin: With my marbling work I was interested in tapping into the elemental forces of the world, whereby dropping ink into a water bath activated the forces of gravity, cohesion and adhesion to form the aesthetic character of the work. The inks swirl and combine in patterns that evoke galaxies, but also microscopic processes of the body, tapping into and rendering an energy that has been operating for millions of years.

My interest in agates and marble stone also stem from the same durational process that I am trying to evoke and imitate. I am basically collaborating with the universe, creating something that looks at once natural, but also rendered and computer-generated.

Kerstin Brätsch, Work in progress, Fossil Psychic for Christa (Stucco Marmo), artist’s studio, Rome, 2018. Photo: Daniele Molajoli

Kerstin Brätsch, Work in progress, Fossil Psychic for Christa (Stucco Marmo), artist’s studio, Rome, 2018. Photo: Daniele Molajoli

With the digital, the idea of the original is compromised: we work with instantiations of an original which misplaces that same idea. The gradient brushstrokes in my paintings – which look like a digital effect – become original again when I sculpt them, as I do with the stuccos. To use traditional craft techniques is to engage in alchemistic processes – the temperature needed for the oven to create glass, or the chemicals required to mix pigments, or the amount of time we must allot to set stucco – and this relates to the occult, insofar as we are dealing with secret recipes. I’m interested in engaging with the power of the unknown, and then manipulating its force with an awareness of contemporaneity. I engage universal forces in my marbling work, light and lava in my glass work, and try to horizontalise them. I enter them into an equation: if lava is glass, and glass is painting, then lava is painting.

Gina : There’s one work in particular from the series Fossil Psychic for Christa (Stucco Marmo) that reminds me of the nebulous shapes of flints, the animal-mineral process that forms them: a molten stone filling the cavities left by creatures burrowing underground. These symbiotic forces in nature seem quite close to how you engage with materials and how your work communicates. It feels like you and these other elements are complicit in what’s signified; in that particular work, it could be a serpentine organism in a subterranean tunnel as much as a fragment from a calligraphic script.

Kerstin: That ‘painting’ looks three-dimensional and frozen in time, fossilised or crystallised. To come full circle: the stucco could be read as a materialised, flattened marbling drop. In this particular work (but also in others) the brushstroke is turned into and reads as a quasi-trace of life and time, the remains of something that has been alive or active, the

leftovers of a process that has already happened. I really like how you talk about the work as like a mark left by a living creature, say a mole or termite, and turned by nature into a fossilised trace. In this analogy, not only is time being addressed and scrutinised, but also space. The works could also be seen as just squiggles or a graffiti tag, and I like that it can toggle between being read as cartoony characters or pinball machines and as the geographical traces of millions of years of natural forces.

Gina : You call the stucco works Fossil Psychics. I love that – as if they’re inert traces of long-dead beings that can still communicate through their morphology. A kind of divination, like reading tea-leaves or rune stones. And they do read both as images and as cyphers. The stucco brushstrokes are like hieroglyphs, pictograms; like in the work that invokes a peacock spider but is also a character from a Maya codex – both, and many other things too. There’s an implicit language in nature’s processes, in the behaviours of animals, organisms, materials, that can be intuited without knowing it rationally. An understanding that’s derived from an empiricism in the body – knowledge from encounter, not intellect. As I’ve been working on this exhibition, I’ve thought a lot about how patterns in the natural world convey preconscious meaning that’s encoded in our bodies, in animals, plants and rocks, embedded in DNA, in millennia of evolution, through cross- species communication. How plants evolved to create flowers – colourful abstract forms that are attractive to their pollinators – and how that coincided with the proliferation of insects. Co-evolution, or perhaps a de- centralised (Gaian) consciousness working through all things, both animate and inanimate. How the

instinctual part of us knows the markings on a snake mean danger. That’s not learnt in the scope of an individual life – it’s inherited through genealogy. We co-evolved with snakes. And this archetype emerges in ancient mythologies worldwide: the tree of life and tree of knowledge and the serpent in Genesis is just one example and is a retelling of an even more ancient tale. The personification of Ayahuasca, the sacred vine of the Amazon, with the serpent, is another. The serpent and the tree are intrinsically bound and are fundamental to what has made us human. It comes back to this correlation between sound and image – as a snake’s markings signal danger, so too when we hear the call of an animal do we know whether it’s a mating cry or some kind of aggression. It’s instinctual. We are human – fundamentally animal – and inherently bound to the vegetal world. This is where aesthetics come into their own.

Kerstin: Your thoughts on serpents bring a couple of things to mind. I was recently at the Brancacci Chapel in the Church of Santa Maria del Carmine during my residency in Florence. There I came upon two frescoes made by the Renaissance painters Masolino da Panicale and Masaccio situated directly across from each other, both depicting Adam and Eve. Masaccio (1401–1428) was the student of Masolino (1383–c. 1447), but their styles are completely opposed. While Masolino presents a very idealised and peaceful version of the story, with a friendly snake hanging above the whole scene, the young Masaccio presents a radical break: Adam and Eve caked in sweat and dirt, their faces contorted with the pain of the real world and the snake curiously absent.

Another reference that I always return to is Aby Warburg and his ‘Lecture on Serpent Ritual’ (1923), a study of the 16-day religious ceremony practised

Kerstin Brätsch, Work in progress, Fossil Psychic for Christa (Stucco Marmo), artist’s studio, Rome, 2018. Photo: Daniele Molajoli

Kerstin Brätsch, Work in progress, Fossil Psychic for Christa (Stucco Marmo), artist’s studio, Rome, 2018. Photo: Daniele Molajoli

Kerstin Brätsch, Brushstroke Fossil For Christa (Stucco Marmo), 2018. Plaster, pigments, glue, wax and oil, 59.4 x 104.9 x 5.1 cm, 50 x 63 x 5.1 cm. Photo: Daniele. Molajoli; Courtesy Gavin Brown's enterprise

Peacock spider, Jurgen Otto: peacockspider.org

by the Native American Hopi tribe in Arizona. Since snakes are considered guardians of the spring, the ritual is performed every two years to pray for rain. Because the tribe believes their ancestors originated in the underworld, they rely on snakes, whom they regard as brothers, to take their message to the gods and spirits that reside there. In the ceremony the snakes are first carried by hand and then in mouths so as to impart the message to be delivered. Warburg was interested in the way that snakes, in their zig-zag shape, symbolised a lightning strike and danger, while at the same time also rain and corn. He considered the serpent the uncanny animal, and moved beyond the Western conception of the snake as the root of evil to be the site both of violence and regeneration.

Gina : You’ve mentioned that you’re developing a 2000-square-metre garden inspired by the 12th- century mystic and polymath Hildegard von Bingen, and that it includes astronomical observatories. Von Bingen is an important touchstone for the exhibition, which draws from a medieval worldview and gives attention to marginalised ways of being, knowing and experiencing that are, for the most part, precluded by the presuppositions (and superstitions) of secular modernity. Her cosmology is illustrated in the illumination and commentary Cultivating the Cosmic Tree – a mandala that situates the tree as a world-axis, symbolising the generative force of the cosmos and human nature as a microcosm of the universe (macrocosm). That reciprocity between plants and the astrological realm was at the core of her healing practice.

Kerstin: The garden brings past, present and future together. Its layout is designed to evoke a giant painting facing the sky, enlarged and translated

into plants. It would exist as an amalgamation of different sections: mosaic paths, a children’s hedge maze, Japanese garden, resting lawn, wildflower meadow, medieval medicinal herb garden, espaliered fruit trees, a café, and an area with Jantar Mantars. Originating in Jaipur, India, in 1623, Jantar Mantars are architectural astronomical instruments, similar to an observatory, used to compile astronomical tables and predict planetary movements.

The garden will be located on a historical trade route between France and Rome and this is referenced in the various floor mosaics. Their designs are based on my stucco monsters and brushstrokes – the works we were discussing earlier – which are in turn based on my oil on Mylar paintings. Enlarged beyond a human scale and translated into mosaic, these works would be built specifically as paths to be walked on. Another nod to the past is the medieval medicinal herb garden, based on Hildegard von Bingen’s knowledge. My hope is that the garden will be used as an educational tool for visitors as well as being a multisensory experience for all kinds of people, with a special emphasis on access for the disabled, elderly and children.

I want to make sure that it’s pulled into the ecological present by providing edible ingredients for use in a café on a daily basis. The present would therefore be represented by the ever-growing plants themselves. The Jantar Mantars signal the future. Within the grounds they would function as a forecast of the future but also as a playground for children or a panoramic view of the whole garden for visitors.

Gina: I love that you’re installing the Jantar Mantars in the garden. Plants are also oriented to the stars; they grown upwards and perform a kind of alchemy,

matter, with an array of geometric forms and patterns. The sacred geometries you see in plant morphology embody the microcosm–macrocosm principle, the metaphysical idea of infinity manifest in a tangible, material form. It’s a mathematical principle that’s inexhaustible by extrapolation in either direction; both expansion and reduction lead to infinity on both horizons. They’re the same patterns described since antiquity as a ‘music of the spheres’ – a way of tracing the movements of the planets and the operation of the universe on the human scale in terms of harmonic intervals perceived aurally and visually as geometric, mathematical patterns.

Kerstin: I envision the garden as a living painting or organism that is constantly growing and changing with the seasons and over the years. It would be a space that responds to different forces, elemental as well as man-made, where the garden is shaped by the weather but also by its caretakers as well its visitors. In this way, the garden is another iteration of my probing of painting, primarily as a social body. The garden will outlast even myself, and inherent in this idea is that it will evolve in its look and function. It’s a map for a future painting, a living painting, one where its lifespan is stretched into a different paradigm of time.

Gina: Plants are really the first station of life on earth. They created our habitats, our food and the atmosphere we breathe. Von Bingen referred to a divinity in the vegetal kingdom as Viriditas, a kind of truth and healing power in nature that can bring about planetary attunement. It’s beautiful to think of your garden having a lifespan that will unfold after you’ve planted it. In that gesture you seem to acknowledge that the plants were here first, and they’ll be here after us too.

Kerstin Brätsch, Work in progress, Fossil Psychic for Christa (Stucco Marmo), artist’s studio, Rome, 2018. Photo: Daniele Molajoli

Hopi (Moqui) Indians, Inake dance, c. 1910-25. Courtesy National Photo Company Collection (Library of Congress)

A view over the constellation-pointers at the Jantar Mantar observatory. Photo: Christopher Walker

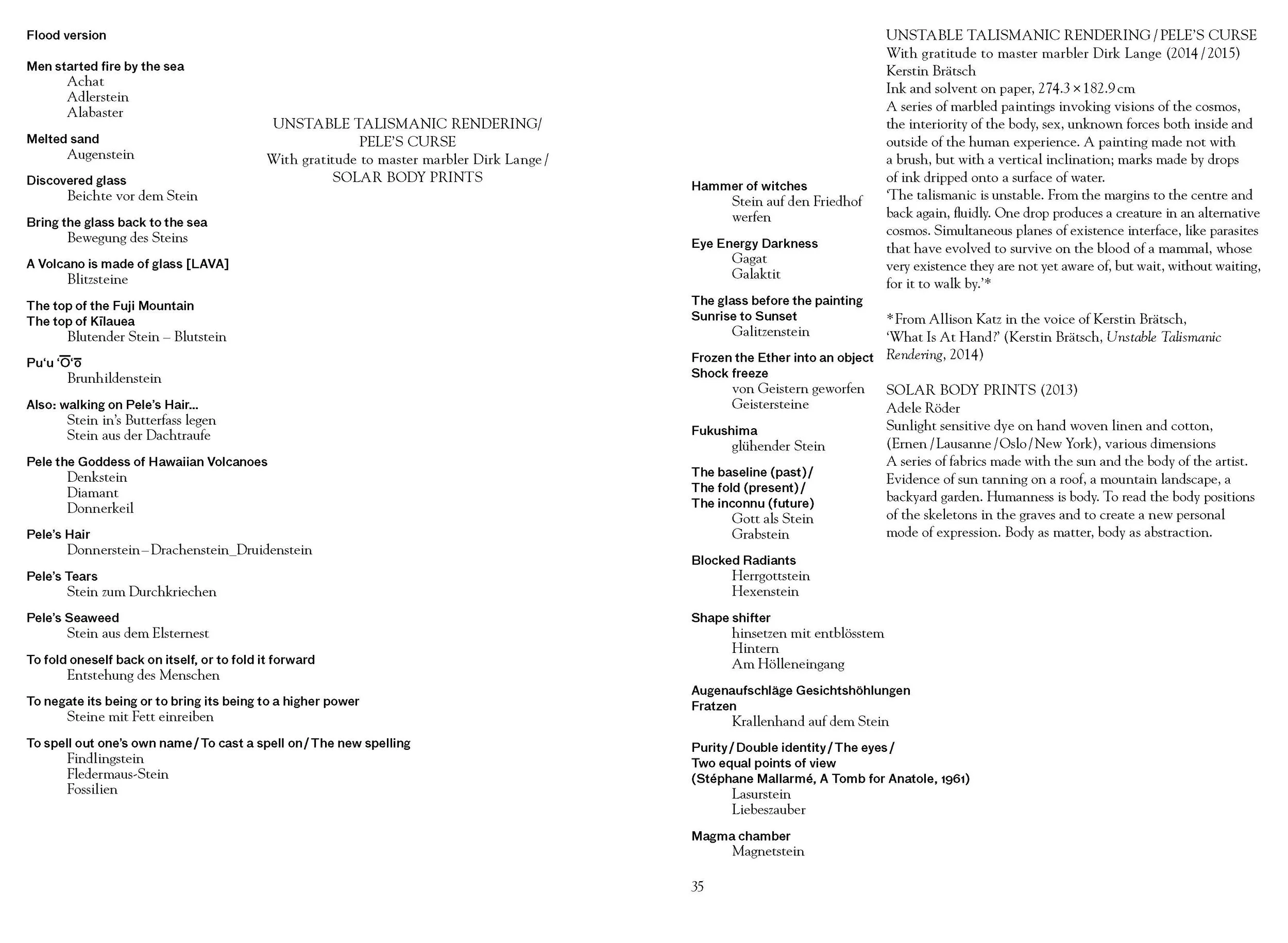

Das Institut

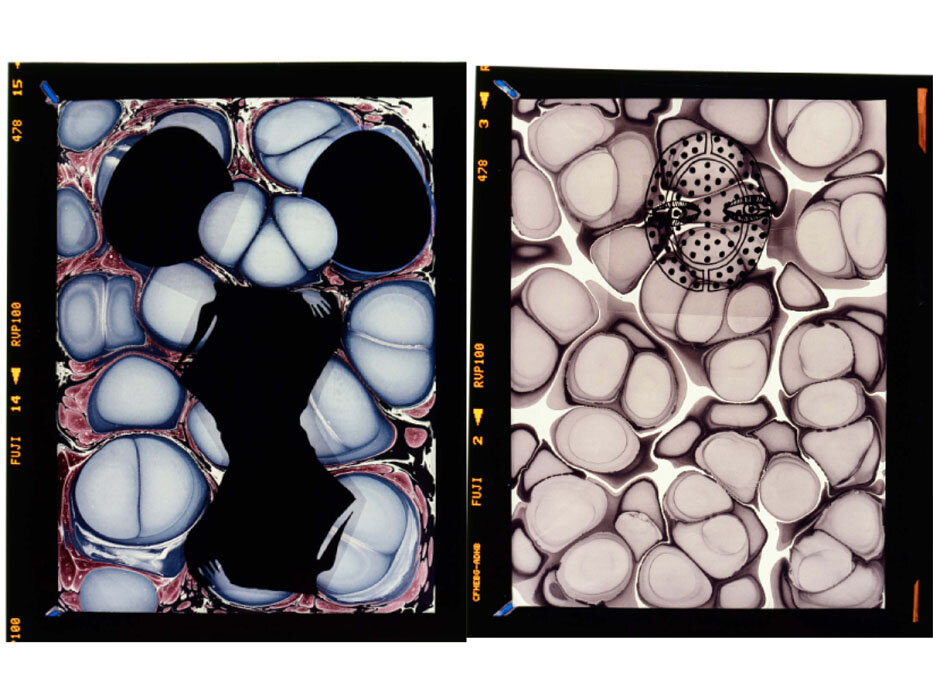

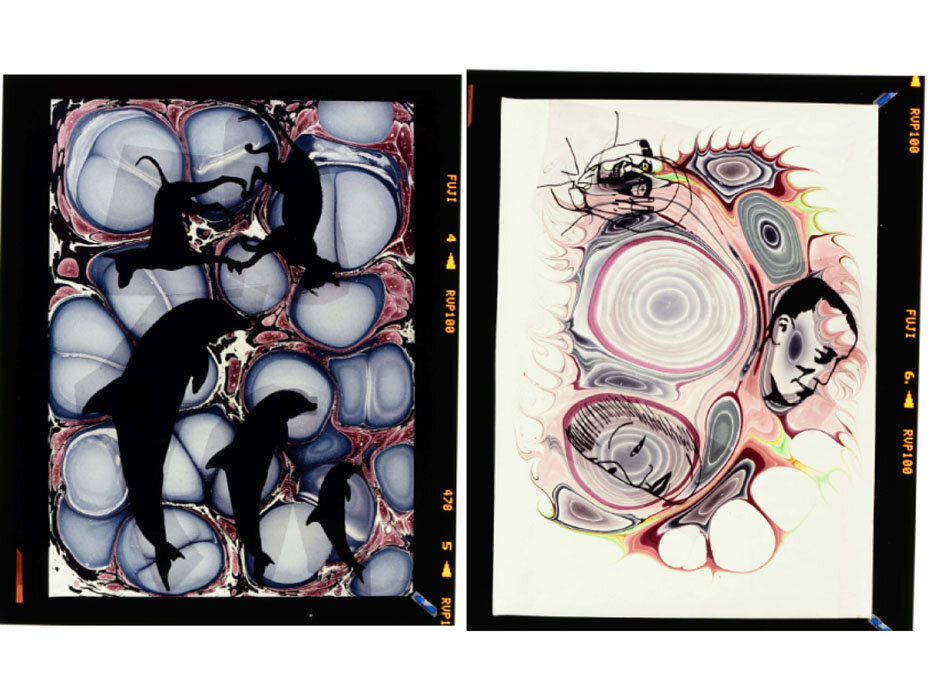

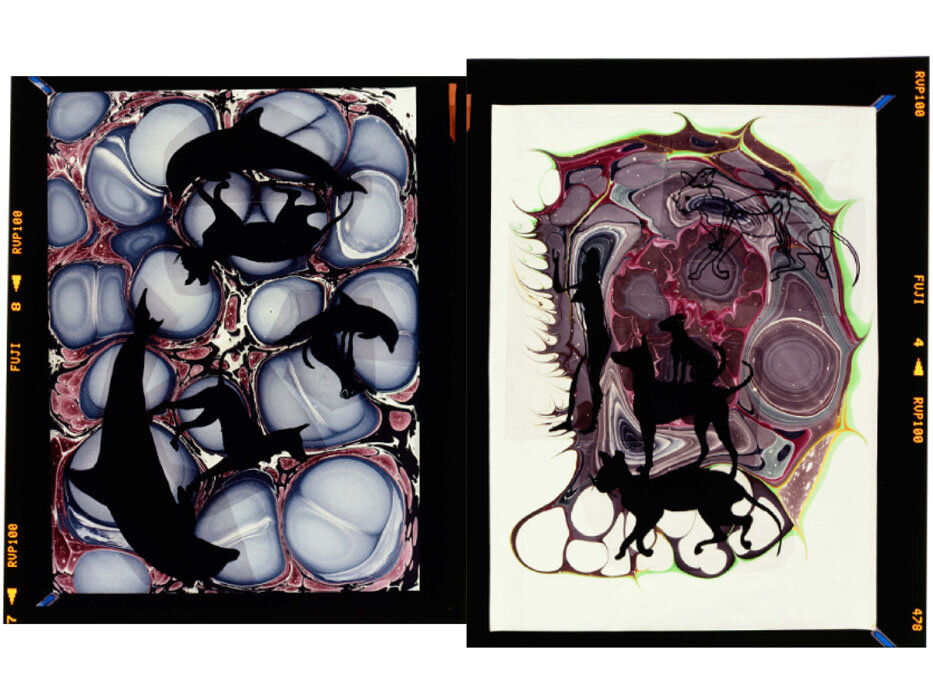

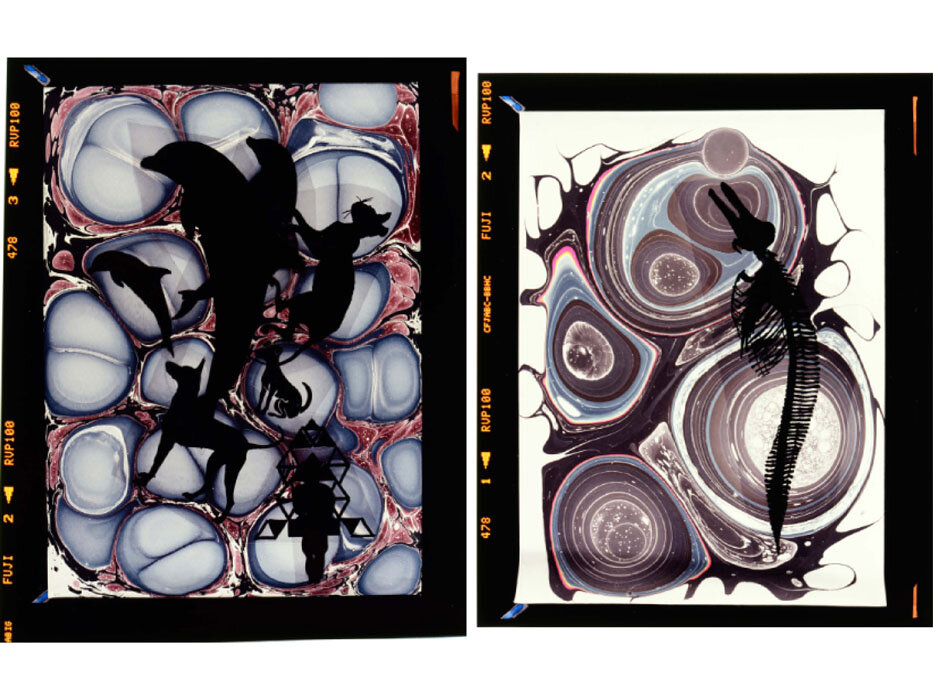

D A R K C O D E X , from Almanac, Eclipses and Venus Cycles series, 2016

Marker pen on transparency, ink and solvent on paper, 68×50cm turned into 2 medium format slide projections (80 slides each)

Kerstin Brätsch and Adele Röder have worked collaboratively as DAS INSTITUT since 2007. Their work is concerned with the ineffable, the felt or intuited aspects of being and how bodies and matter communicate without words through symbolic forms that emerge in the space between figuration and abstraction. Dark Codex is a medium format slide projection from the artists’ Almanac, Eclipses and Venus Cycles series reconfigured here for The Botanical Mind Online.

“A mapping of the world by drawing out subjectivity. An abstract forecast taken from the current condition of the universe. The flip of an internal microview of the body into a macro view of the universe. A secret interpretation, like a mystic chant and a talismanic language. Private and cosmological signals. DARKCODEX is animalistic, ritualistic, pop, optical, symbolic, and story-based like a false monument.”

Next chapter